Transmission

Capacity and contracting may slow progress

toward clean-energy goals

Across the West, states, utilities, and local governments have adopted clean-energy policies in response to the impacts of climate change, with the goal of moving the electricity supply increasingly away from generators that burn fossil fuels to renewable energy, particularly wind and solar power.

The state of Washington’s goal is 100-percent clean electricity by 2045. In Oregon, it’s 2040. In California, it’s 2045. Some cities also have adopted clean-energy policies. Missoula, Montana, for example, adopted a policy in 2019 calling for 100 percent clean energy in the city by 2030. Boise’s goal for clean energy is 100 percent by 2035. For the Idaho Power Company, the largest utility in the state, the target date is 2045. Montana, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah all have adopted standards for adding renewable energy to the power supply, with various goals and deadlines.

As more and more renewable energy is added to the West Coast power supply, the existing transmission system will be challenged to move it all from generation to load, as the power system engineers say.

While the Northwest is blessed with an abundant supply of hydropower, solar and wind power have become so inexpensive that they are beating the price of practically every other type of power in the wholesale market, making many inefficient thermal plants fueled by coal uneconomical to operate. Many coal-fired generators are planned for retirement. In 2018, the region’s coal-fired generation totaled around 7,000 megawatts of capacity. Since then, with the retirement of Colstrip units 1 and 2 in Montana, Boardman in Oregon, Centralia unit 1 in Washington, and Idaho Power’s exit from North Valmy unit 1 in Nevada, total coal-fired generation is now just under 5,000 megawatts. By the end of 2028, the total will decrease even more to around 2,400 megawatts through the planned retirements of Jim Bridger units 1 and 2 in Wyoming, Centralia 2 (Washington), and North Valmy unit 2 (Nevada). While some coal generators still will be operating in 2029, the future of those generators is uncertain. With the planned retirements, the capacity of coal-fired power plants in the region will be reduced by more than 60 percent over the next decade. Wind and solar are expected to replace much of the coal-fueled generation.

However, one issue has the potential to derail swift progress toward the ambitious clean-energy goals: the potential for insufficient transmission capacity combined with inefficient transmission contracting. That is, the existing transmission infrastructure may not be sufficient to move the thousands of megawatts of new renewable energy from the remote locations where it will be generated to the places where it will be consumed, and even if it is, the current system of contracting for access to transmission sometimes leaves lines fully contracted but not fully utilized.

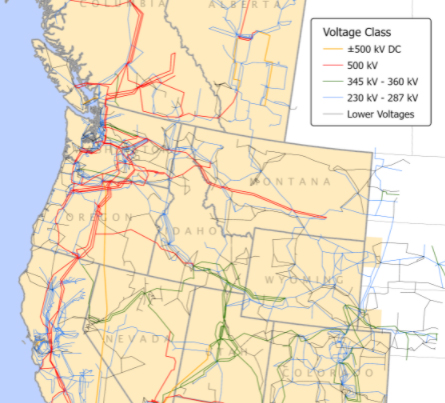

The Northwest spent billions building transmission to connect to the rest of the West. High-voltage transmission enables power to be bought and sold across vast areas and helps avert shortages. When one area needs power, another area usually has it to sell. But as more and more renewable energy is added to the West Coast power supply, the existing transmission system will be challenged to move it all from generation to load, as the power system engineers say. Imagine pouring water into a funnel – the water backs up as it pours through the narrow opening because the funnel can’t handle all the water at once. In this analogy, the water in the funnel is power, and an increasing percentage of it will be generated by wind and sunshine in the future.

Wind and solar don’t behave like thermal generators, with their constant fuel supply. Thermal plants can produce power more or less constantly; wind and solar can’t. Solar doesn’t generate overnight; wind doesn’t generate when the air is still. What that means is that in order to create a constant output, a lot of wind and a lot of solar will have to be built, and energy storage – large batteries, for example – will be needed to ensure a constant flow of power. Fortunately, the Northwest is in a better position to deal with this new reality than other parts of the country because the huge Columbia River hydropower system can serve as an energy storage reservoir – within limits prescribed to protect migrating anadromous fish. Then the question arises: even with adequate energy storage as backup, can the existing transmission system handle all that new water in the funnel?

The answer is somewhere between probably not, maybe, and yes.

First, some background

High-voltage transmission lines connect 14 western states, two Canadian provinces and a portion of Mexico. Within this vast electricity machine, transmission is managed by the owners of the lines in geographic divisions called control areas, or balancing authorities. Entities within these areas – often utilities but in some areas the U.S. Department of Energy – ensure that power system demand and supply are balanced in the areas of the transmission grid they control. This is important because if supply and demand become too far out of balance, equipment on the transmission and distribution system will disconnect, creating local or widespread electric power outages. Balance is an important concept. When demand increases in the Southwest, say in summer, power generators in the northern states increase their output. When the colder northern states need power in winter, power generators in the Southwest can increase their output.

Demand for power fluctuates constantly – not just seasonally, but also weekly, daily, hourly, and minute by minute. And, power must be provided at a constant, or near-constant, 60 cycles per second. This is called frequency, and if the frequency varies too far above or below 60 cycles, our devices that use electricity, from cell phone chargers to ovens and countless other electronic devices, will self-destruct.

For a deeper dive on transmission, see the Transmission section of the 2021 Power Plan

Frequency is controlled by maintaining a stable net power interchange between neighboring balancing authority areas. The basic test of success for this is called the Area Control Error (ACE). ACE is a measurement, calculated every four seconds based on the imbalance, or deviation, between load (demand for electricity) and generation within a balancing area. Reliability standards for ACE are set by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) and the Western Electricity Coordinating Council (WECC). The premise of these standards is that deviation should be very close to zero. ACE is maintained through a combination of actions, some of them automatic and some controlled by balancing authority transmission operators.

Maintaining a near-zero ACE while sharing power across balancing authorities is complex now, but the addition of more and more megawatts of variable-output renewable energy to the power supply will only increase the complexity of transmission management. And transmission experts say that as more renewables are added to sunny and windy open but remote areas, new transmission lines will be needed, too.

High voltage, high controversy

Building new lines takes time and can be controversial. It’s not just an issue of high cost, but also one of ‘not in my backyard.’ In 2015, the Bonneville Power Administration proposed to build new lines along the Interstate 5 corridor to ease the strain on existing lines. Several alternative routes were proposed, including one that would have skirted developed areas and passed through the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Hundreds of people attended public hearings, and many if not most angrily voiced their opposition. In the end, the lines were not built and Bonneville focused instead on improving the capacity of existing lines.

Improving the capability of the existing system as an alternative to building new lines is something the Council has explored through analyses now incorporated in the Draft 2021 Power Plan. It’s a concept some commentors discussed during public hearings on the draft plan, including, for example, Fred Heutte, senior policy associate with the Seattle-based NW Energy Coalition. Heutte said it’s clear that more transmission is needed, but that before building new lines it’s important “to get more out of the system we have.”

“Bonneville has done a lot of work on improving power flows, for example, but we will need new transmission to deliver the new renewables to where they are needed,” Heutte said. “We need to use the existing system as best we can and decide in the next few years what we need in the future.”

An alternative to building new lines is improving the capability of the existing system.

Others, including the Council, also recognize that the transmission system needs to be expanded or, if new lines prove too expensive or controversial to build, improved. In the Draft 2021 Power Plan, the Council comments that while it has no authority regarding transmission planning or construction, it is clear that adding renewables to the power supply “will depend on sufficient transmission capability on the system to deliver electricity from the source of generation to the locations where electricity is needed.”

Also important, though, is the fact that no power plant is built without available transmission to deliver its output. That is, before a developer invests millions in a new power plant of any kind, transmission must be arranged. That’s important not only to ensure the new power will be delivered, but also for financing construction of the generating plant. Investors won’t support a new plant that can generate but not deliver its power.

Non-wires alternatives

Like the weather, power planners can envision a perfect storm brewing for our power supply – retiring thousands of megawatts of thermal generation, adding thousands of megawatts of renewable generation, and a grid of congested transmission lines connecting the West, that might not be adequate to handle all the new power. It should come as no surprise, then, that attention is turning to exploring alternatives to building new lines – to get more out of the system we have, as Heutte of the NW Energy Coalition suggested.

The Council’s draft plan recognizes this issue, commenting that it is not unusual for transmission access to be fully contracted on a long-term basis without being fully utilized. Because of this, developers of new generating plants may have to wait several years for access to transmission, slowing or halting construction.

The draft plan suggests exploration of alternatives to new construction of transmission, called “non-wires alternatives.” These include battery storage and targeted demand response, which is the voluntary and temporary reduction of power use during times of high demand, usually by customers that use large amounts of power and usually in return for compensation. In the Draft 2021 Plan the Council estimates demand response potential as 3,721 megawatts of summer load reduction and 2,761 megawatts of winter load reduction. Demand response could help relieve transmission constraints and defer transmission and distribution system upgrades, according to the draft plan.

Another non-wires alternative is utility-scale batteries that are built at known areas of transmission congestion. These strategically placed energy storage facilities can help alleviate pressure on the transmission system and delay the need for new transmission. Batteries can store energy for release when, for example, the wind dies and the sun sets. The draft plan recommends that the region “… consider the role of battery storage, targeted demand response, and other demand-side resources to address existing transmission capacity challenges.” The Council explored battery storage in developing the draft power plan; see the paper on utility-scale battery storage.

Steve Wright, general manager of the Chelan Public Utility District in Wenatchee and a former administrator of the Bonneville Power Administration, agrees that non-wires alternatives should be investigated, but as a component of a multifaceted approach.

“We can’t do this with non-wires solutions alone,” Wright said. “Demand-side management will be a critical part of this. We’re going to put a lot of megawatt-hours onto the system from remote locations where transmission is either nonexistent or weak today. Somehow those megawatt-hours are going to have to flow to load.”

Strategically placed energy storage facilities like large batteries can help delay the need for new lines.

Changing management of transmission also could help, if it is done carefully and in a way that meets the unique needs of the Northwest and West Coast power supply.

In a 2019 study of resource adequacy in the Northwest, Energy and Environmental Economics, a San Francisco energy consulting firm, noted that there are constraints that may prevent a generator in one part of the region from being able to serve load in another part. The solution is to build new generating plants and transmission lines, but there may not be enough available land for it all.

This study concluded that while deep decarbonization of the power grid – the goal of Washington, Oregon, California, and some utilities and local governments – is feasible without sacrificing reliable electric service, achieving a carbon-free power supply (absent technological breakthroughs) using only wind, solar, hydropower, and energy storage “is both impractical and prohibitively expensive.” The report continues, “firm capacity – capacity that can be relied upon to produce energy when it is needed the most, even during the most adverse weather conditions – is an important component of a deeply-decarbonized grid.”

Delivering power economically and reliably from where it is generated to where it is needed means resolving constraints like multiple pricing transactions as power passes through individual transmission balancing areas, and lengthy queues for access to transmission. This will require better coordination, according to the study.

But, how to achieve better coordination?

Is a West-wide transmission organization the answer?

One way to possibly clear the transmission queues and open more access to the lines is to improve coordination of transmission access through creation of a regional transmission operator (RTO). In the draft power plan, the Council encourages transmission owners, power plant developers, utilities, and others to explore the idea.

It’s an idea that resonates with power experts around the region. For example, Joe Lukas, general manager of the Western Montana Generation and Transmission Cooperative in Montana, supported the idea at one of the Council’s power plan hearings as a means of dealing with what he called “the transmission challenges” in the region. “Many of us believe the Northwest really needs to look into an RTO,” he said.

Elsewhere in the West, some states – Colorado and Nevada, for example – have passed laws requiring electric utilities to join a regional transmission organization by 2030. A study funded by the U.S. Department of Energy issued in September 2021 estimated that power consumers in the West could save between $1.4 and $2 billion annually from the improved coordination of generation and transmission that RTOs provide.

The concept of a West-wide RTO also is endorsed by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), an international environmental advocacy group with its West Coast headquarters in San Francisco. NRDC has been following transmission issues for years and in 2016 issued three broad recommendations for the West:

- State legislators and utility regulators should approve consolidation of the 38 separate transmission ‘balancing area authorities’ in the West that control generation and load in their territories (NRDC says the current situation is like having a bus with 38 drivers)

- Authorities should approve expanding the California independent system operator to the rest of the West

- A new RTO should focus on transmission only and not establish a market for capacity – or peaking power to meet high demand – which NRDC believes is not necessary to maintain reliable electric service

NRDC believes an RTO could mean reduced costs for consumers, fewer new transmission lines and expensive power plants, and reliable and cost-effective integration of renewable energy into the grid.

As might be expected, the question of how to improve the transmission system and access to it ultimately is both economic and political. Should new lines be built? Where would they go? How much will they cost? Who will decide, and how?

In a 2021 study of how to maintain electricity resource adequacy as fossil fuel generators retire and renewable energy plants proliferate, the Reston, Virginia-based Energy Systems Integration Group concluded that there is economic opportunity in increasing regional coordination and relying on imports to meet reliability needs.

“Key to unlocking this economic opportunity is transmission, to enable flows between regions and create interregional resource diversity,” according to the study. “The value of sharing between adjacent regions was a major driver for the formation of independent system operators and regional transmission organizations,” the report continues, adding that “… ultimately utility regulators, policymakers, and system planners must determine the level of reliance on neighbors that is acceptable, given the local conditions and resource mix. There is no right or wrong answer.”

Interregional sharing would have helped with the Texas cold snap earlier this year, according to the authors. While the middle of the country shivered, the East Coast experienced normal temperatures and had surplus electricity. But it could not be shared with the Midwest. “Additional transmission capacity between regions could have mitigated some of the resource adequacy failure,” according to the study.

While the concept of interregional sharing seems simple, the question of who would deliver power and who would receive it – and under what conditions – is tricky.

“While the pooling of resources improves reliability, it raises questions about how to appropriately share resources during times of resource adequacy risk,” according to the study. “This introduces a policy and regulatory challenge about how to balance reliance on neighbors [with] self-sufficiency.”

In the draft power plan, the Council assumes that utilities and existing transmission planning organizations will work together to ensure appropriate investment is made into the transmission system to, at a minimum, maintain the current ability to deliver electricity around the West. The Council did not study expansion of the transmission system in the draft plan, but others have called for such an analysis in response to the impending addition of thousands of megawatts of renewable resources to the power supply.

For example, a coalition of environmental and labor organizations in California sent a letter in August to the state Legislative Assembly encouraging the construction of new transmission lines to support the state’s renewable-energy goals. In their letter, the groups argue that if new transmission is not built, natural gas generators will have to stay online longer in the day to make up for the solar power that is lost after sunset, and some economically disadvantaged communities won’t be able to enjoy the benefits of low-cost renewable energy. Not only is the state’s transmission system inadequate to handle all the new renewable energy slated to be built – more than 11,000 megawatts – but transmission planning is bogged down in the state’s complex energy bureaucracy, and the Assembly could help speed the process, the groups asserted.

Volatility, political and economic

The politics of the transition to more renewable energy is recognized elsewhere, too. For example, former Congressman George Nethercutt, today a Spokane attorney, recently wrote in the Spokesman-Review newspaper that “it’s important to ensure that Washington State’s transition to renewables is achieved without compromising reliability. To maintain reliability, we must continue diversifying, adding more wind, solar, and dispatchable resources (including natural gas as a bridge fuel) as part of a balanced energy mix.” To ease this transition, Nethercutt wrote, Washington should join or help establish a regional transmission organization for the West. An RTO would benefit consumers by increasing competition among transmission suppliers, which would likely drive down the cost of power, he wrote. “Increased competition will ultimately provide lower energy prices, improve reliability, increase investment in renewables, and move Washington state toward a cleaner energy future,” he wrote.

But this matter is neither settled nor easy.

Chelan PUD’s Wright, who has worked in the energy industry for more than 40 years, wrote in a response to Nethercutt that RTOs are complex, and that in regions where they have been implemented around the country they are not implemented in the same way.

“They address such topics as transmission planning, operations and pricing, short-term electricity trading and managing the instantaneous balancing of supply and demand necessary to maintain reliability,” Wright wrote. “While these functions are performed by utilities in the Northwest today, the question is whether to transfer those functions to a centralized entity.”

RTOs are organized around four key functions, he wrote:

- Expanded use of organized markets for short-term electricity trading

- Establishing minimum standards that assure sufficient supply to maintain reliability

- Establishing control of decision-making

- Transmission planning

With thousands of megawatts of renewable energy set to come online in the near future in response to clean-energy policies, the wholesale power market likely will be awash in inexpensive energy, particularly mid-day when solar plants are generating at their peak. This makes it challenging to maintain power system reliability and also creates yo-yoing price signals that stifle capital investments. And then, if hot or cold weather drives up demand, or if generating plants experience unplanned outages, supply and demand can get out of synch, causing prices to skyrocket.

“It would be incredibly unwise and lacking historical perspective to risk forfeiting the economic and environmental benefits the Northwest enjoys, particularly from our low-cost, reliable, carbon-free hydropower system, by turning over electricity operations control to a system run by California politicians.”

– Steve Wright, Chelan PUD

“The last time the Northwest saw this kind of market behavior was in the late 1990s prior to the 2001 West Coast energy crisis, when tens of thousands of people lost their jobs and environmental protection was compromised,” Wright wrote. “Many citizens found it hard to understand why their lives were severely disrupted through no fault of their own.”

This kind of market volatility not only wreaks havoc with wholesale power prices, it brings into focus a key political question: How would a West-wide RTO coordinate decisions about access to transmission and the flow of power from willing sellers to willing buyers across more than a dozen states and hundreds of utilities serving millions of customers?

Could it work? Wright’s answer is a careful ‘maybe.’

“The only operating RTO in the West is in California [the California Independent System Operator, or ISO], the state with the highest electric rates in the country,” Wright wrote. “The Northwest and California have a long electricity trading history with elements of both synergy and contentious disputes. The California RTO is ultimately governed by California elected officials representing their constituents. It would be incredibly unwise and lacking historical perspective to risk forfeiting the economic and environmental benefits the Northwest enjoys, particularly from our low-cost, reliable, carbon-free hydropower system, by turning over electricity operations control to a system run by California politicians.”

In Colorado, where state law requires utilities to join an RTO by 2030, the chairman of the Colorado Public Utilities Commission, Eric Blank, is thinking along the same lines. In November, he told a reporter for Market Intelligence, a publication that focuses on the energy industry, that his state will need to see governance reforms at the California ISO before settling on an RTO approach for his state.

In the Northwest, utility executives might be similarly reluctant to join an expanded California transmission organization. In fact, the Northwest has a running start on its own RTO – Northern Grid, a transmission planning organization that could connect to other transmission planning activities in the West.

“I think the role for that organization is going to grow substantially because we haven’t been building a lot of transmission,” Wright said. “We’ve been building some, but not a lot in the last decade, and so if we are going to have a massive transmission investment program there will be a big role for a transmission planning organization.”

Pressure on Bonneville

As the largest transmission owner in the Northwest – about 15,000 line miles – the pressure is building on the Bonneville Power Administration to provide transmission for all the new renewable energy that is coming. In a study this year, Bonneville identified 116 requests for transmission totaling as much as 5,842 megawatts of capacity, mainly from proposed solar and wind plants that would be built east of the Cascades to serve load west of the mountains. Meeting these requests will require an investment of $845 million in system upgrades, and most of it would go to upgrade a line that runs between Olympia and Centralia, Washington, Bonneville reported. That upgrade would be needed if and when several thermal plants west of the Cascades are retired, a requirement of Washington’s Clean Energy Transformation Act.

Clean-energy policies in Washington and Oregon call for significant decarbonization by 2030. Investor-owned utilities are including large amounts of renewable generation in their integrated resource plans as they work to wean themselves from thermal generation to meet state goals.

Energy consultant Randy Hardy of Seattle, a former Bonneville administrator, told the Clearing Up newsletter in November that access to transmission, particularly from new generating plants east of the Cascades to serve load centers west of the mountains, will be a growing problem for investor-owned utilities like Puget Sound Energy and Portland General Electric as they work to meet state clean-energy goals by 2030.

“It’s a pretty straightforward problem,” Hardy said in an article by Clearing Up Editor Steve Ernst. “The state Legislatures wrote clean energy laws without adequately considering the transmission constraints that currently exist. It will take 10 to 15 years to build a new transmission line, which just doesn’t sync with the 2030 clean energy dates.” Spencer Gray, executive director of the Northwest and Intermountain Power Producers Coalition, agreed with Hardy in comments to Clearing Up. “I’m still hopeful there will be tools on the table, but as of today, it really concerns me that we don’t have the right grid to make meeting the standards possible,” Gray said. “We simply can’t make the 2030 goals without building more transmission capacity.”

— Story by John Harrison, January 2022 —