- 2-A. Competition in Electricity Markets

- 2-B. Restructuring of the Natural Gas Industry

- 2-C. Gas Turbine Technology

The Northwest's electric power industry is constantly evolving. That is nothing new. However, the pace of that evolution is new – a pace many believe is more rapid than at any time in memory. What has been a regulated monopoly, is increasingly becoming a competitive market. The three interacting factors driving change in the electric utility industry are:

- Wholesale electricity markets have become competitive due to regulatory changes that opened the industry to new players. This opening of the wholesale market, combined with lower overall prices for new sources of electricity, has resulted in significant pressure to open retail markets to competition as well.

- The availability of adequate supplies of low-cost natural gas has driven down the marginal cost of new generating resources. In addition, low gas prices have made it economical to operate at very low costs older gas-fired generating plants already in the West Coast system. This has created an abundance of low-cost electricity in the West.

- Finally, gas turbine technology has improved, resulting in a low-cost, efficient resource that can be built quickly and in relatively small increments to meet growing loads. This has significantly lowered the barriers to entering the power generation business, thus contributing to increased competition.

2-A. Competition in Electricity Markets

Probably no change is more important to the electricity industry and, by inference, to this draft power plan and the goals of the Northwest Power Act, than the evolution toward open competition among electricity producers and distributors. The principal benefits of opening an industry to the pressures of competition are to bring down prices and increase customer influence over the variety, quality and price of services the industry delivers. That has been the clear goal of the federal government's restructuring of both the natural gas and telecommunications industries. It is also the goal of restructuring in the electricity industry. A key lesson of restructuring in other industries is that how restructuring occurs and how regulation changes to accommodate increased competition are important.

The Traditional Regulatory Environment

The electric utility industry, until relatively recently, was made up of regulated monopolies – businesses that were, to a large extent, protected from competition. There was always some competition between electricity and competing fuels for such applications as heating and industrial processes, and even competition among electric utilities to attract new loads. But, historically, there was little competition from non-utility generators of electricity, and almost no one competed to sell electricity within a utility's service territory. The utility's franchise was protected.

The traditional regulatory environment reflected the realities of the industry as it existed years ago. It was an industry that required the construction of large, capital-intensive power plants and the rapid expansion of transmission and distribution systems. The regulatory system that evolved was a cost-based system that offered utilities the financial stability associated with a protected customer base. In return, utilities accepted an obligation to serve all customers in their service territory and regulation that prevents the exercise of monopoly power in the prices they charge. This regulatory framework generally holds true today for both the investor-owned utilities, which are regulated by state utility commissions, and the local public utilities, which are regulated by locally elected boards or commissions.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Bonneville Power Administration is a special case in that it is a federal marketer of wholesale power. Bonneville sells the electricity generated at federal Columbia River hydroelectric dams and one nuclear plant, the Washington Public Power Supply System's WNP-2, to retail utilities and to some industrial and government customers that are served directly rather than through utilities. The federal power marketer is required by law to sell to its public agency customers at cost. Because Bonneville markets the power generated at the federal Columbia River dams, those costs were, until recently, well below the cost of alternative power supplies. This meant Bonneville had a secure market for its inexpensive electricity. Furthermore, most of Bonneville's customers are "full requirements" customers, that is, Bonneville supplies all their power needs.

Regulatory Policy – Wholesale Competition

In 1978, the utility industry's near-monopoly on power generation began to crumble. Congress passed the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) to promote renewable resources and cogeneration and to reduce utility reliance on imported oil. PURPA created a class of non-utility generators that had the right to sell the output of their power plants to utilities at the price the utilities would have to pay to develop their own resources – their so-called "avoided cost." This was an attempt to mimic market-based economics, and it encouraged developers to compete to supply utility resources. While these provisions stimulated wholesale competition, the law was very specific in prohibiting these new producers from selling to retail customers.

The next major federal regulatory change occurred in the National Energy Policy Act of 1992 (EPAct). This legislation created a class of wholesale generators that are exempt from the legal and financial requirements of the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935. Exempt wholesale generators have the ability to structure themselves any way they want, although they are still subject to rate-regulation by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission when they sell their power in interstate commerce. The 1992 Act further eased entry into the wholesale generation business, but prohibited these exempt generators from making sales to retail customers.

The drafters of the 1992 legislation recognized that transmission access was a necessary condition for a fully competitive wholesale power market. If there is to be true competition in generation, generators need to have a way of getting their power to market under terms and conditions that do not discriminate among the owners of generating resources. EPAct gives the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission the ability to require owners of transmission systems to provide access to others wishing to use the transmission system. Again, the legislation was clear that it was addressing transmission access for wholesale transactions only, and that the Commission did not have the authority to require wheeling to retail customers.

In March 1995, the Commission released what has come to be known as the electricity "mega-NOPR" – its notice of proposed rulemaking implementing the open access provisions of EPAct. Although the rules are not yet final, they give a relatively clear picture of the Commission's intent. They require utilities under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's jurisdiction owning both generation and transmission to "unbundle" these functions – separating decisions about generation and transmission within the corporate structure and charging separately for these products.

The utilities are also to adopt transmission tariffs that guarantee "comparability," i.e., charges, terms and conditions for transmission services that are comparable to what the utility applies to itself for these services. The intent is to frustrate the ability of transmission owners to use their transmission to give their own resources an advantage.

The anticipated Federal Energy Regulatory Commission rules will also require establishment of sophisticated information networks that can provide real-time information on the availability and price of transmission capacity. Some industry observers have suggested that functional unbundling and requirements for comparability will not be sufficient to ensure non-discriminatory open transmission access, and that pressure will build for utilities to divest themselves of their transmission assets.

Opening access to the transmission system fosters the need for coordination in the planning and operation of regional transmission grids. The Commission has proposed the formation of regional transmission groups, composed of the users, suppliers and the state regulators of transmission in given regions, to coordinate the planning, expansion and operation of transmission capacity. Many utilities in the Northwest are members of the Western Regional Transmission Association (WRTA) and the Northwest Regional Transmission Association (NRTA).

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission also indicated its intent to address what it perceives to be a transition issue that will have to be resolved – the so-called "stranded investment" problem. Wholesale stranded investments are those that were made to serve wholesale customers who then take advantage of open transmission access to get service from another supplier. If the investing utility cannot recover its investment from its remaining sales, that investment will be stranded.

There are few examples of potential wholesale stranded investments in the Pacific Northwest. One example could be the investment in the Washington Public Power Supply System nuclear power plants, two of which are uncompleted and have never produced power, and another that is operating, but which produces electricity at above the current market price. Fiscal Year 1995 operating costs of the Supply System's WNP-2 were about 3.5 cents per kilowatt-hour, which are higher than the cost of power from new gas-fired combustion turbines, and much higher than current wholesale power prices. The Supply System has set ambitious targets for reducing operating costs. It remains to be seen how successful they will be.

The financing of these plants was backed by the Bonneville Power Administration to meet what was then perceived to be the need for new resources to serve public agency and direct service customers. The capital costs of these plants were melded with Bonneville's low-cost hydropower, causing rates to climb by about 500 percent. Even so, until the advent of competitive pressures, Bonneville could recover its costs, and until recently, keep its rates below the avoided cost of new resources. However, Bonneville's ability to recover those costs fully in today's low-cost wholesale market and fully carry out its other public responsibilities is far from clear.

The changes in the wholesale market brought about by the forces described above have been dramatic. Independent power producers have become the important developers of new generation. More than 100 power marketers have been licensed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. These marketers may not own any generating resources, but they can purchase supplies from a number of producers and put together packages of power products to meet the needs of their customers.

An active spot market has evolved, with spot prices at COB/NOB (the reference point for West Coast power transactions at the California/Oregon border and the Nevada/Oregon border) published daily in The Wall Street Journal. Some utilities have established power trading floors, and the New York Mercantile Exchange is moving toward establishing a futures market for electricity.

The most compelling effect of the competitive changes in the utility industry is that the market price of electricity has fallen. There is clear evidence from the results of various competitive bidding processes that competition among potential developers and marketers has driven down prices. To some extent, this is the consequence of surplus capacity on the West Coast that can be priced at the operating cost plus a small markup. In the past, that surplus capacity might not have entered the market because it was too expensive. Low gas prices and open transmission access are making that capacity a major factor in today's wholesale power market. Many of these developments parallel the experience in the restructured natural gas market.

The development of the wholesale electricity market has been particularly problematic for Bonneville. Because it is exclusively a wholesale utility, it is fully exposed to wholesale competition. Its heavy debt burden for nuclear plants, high operating costs on the one operating nuclear plant and increased costs of salmon recovery efforts are colliding with the falling prices in the wholesale market. The result is that many of Bonneville's direct service industrial and public agency customers are seeking or have obtained power from other suppliers.

In its 1996 Initial Rate Proposal, Bonneville appears to have been successful in putting together a competitive five-year rate proposal. To do so required extensive cost-cutting efforts and efforts to pare back or eliminate some of its other responsibilities. To many, the apparent conflict between Bonneville's public agency responsibilities and the requirements of the competitive market raise questions about Bonneville's continued existence in its historic form. This is discussed more fully in Chapter 7.

Retail Competition

The availability of low-cost power in the wholesale power market is creating pressure for retail competition, i.e., a situation in which individual factories, businesses and even homes might choose who generates their electricity and what power products they buy. Electricity would be distributed to consumers over the same power lines as serve them today, but one consumer might be served by one utility, while his or her neighbor might be served by a different utility, an independent power producer or a marketer. Many believe that the full benefits of a competitive industry will only be realized when retail customers have full access to power markets.

The authority to allow retail competition lies with state and local regulators – legislatures, state utility commissions and the governing bodies of consumer-owned utilities. Not surprisingly, the pressure for retail competition is greatest where retail rates are highest. California embarked on an ambitious effort to restructure its electricity industry to allow retail access first to large customers and then to all customers within a few years. Although not yet complete, it appears almost certain that some form of retail competition will come about in that state.

California is the most ambitious example of competitive restructuring, but there are other states in which retail competition is also being actively considered. Michigan has an experiment in retail wheeling under way. Massachusetts has recently adopted a goal of providing retail customers with the choice of suppliers. The state also adopted principles for the restructured industry and for the transition to it, and has set a schedule for implementation, as has Wisconsin. Rhode Island also has adopted a set of principles for industry restructuring.

While these examples are perhaps the most prominent, regulatory commissions and legislatures across the country are beginning to address the issue, even in areas that do not have particularly high rates. At least 12 states outside the Northwest are investigating the introduction of retail competition.

Given the relatively low electricity rates in the Northwest, this region would seem an unlikely place for pressures for retail access, but even small reductions in price for large customers can translate into significant monetary savings. As a result, some industrial customers in the Northwest are using their market power to obtain the benefits of low wholesale prices. These relatively few large customers are causing much of the electricity industry, even in the Northwest, to act as if retail access were a given.

Puget Sound Power and Light in Washington has customers that have been granted revised rate structures as a result of their attempt to get direct access to the power market through other suppliers. A major customer of Seattle City Light also has sought direct access to the power market. While these are the most public examples, it is likely there are numerous other instances in the region in which utilities and their customers are wrestling with the trade-offs between opening up retail access or making special rate accommodations to retain major customers. Two state utility commissions, Washington's and Montana's, have undertaken inquiries on competition, and the Washington commission has published "Guiding Principles for an Evolving Electricity Industry." [ Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission, "Guiding Principles for an Evolving Electricity Industry," Docket No. UE-940932, December 13, 1991.]

The effects of anticipation of competition are also evident. Utility efforts to "right-size" and cut costs are prevalent. Mergers and acquisitions are under way in the region and across the country, as utilities try to reduce costs through economies of scale and otherwise achieve competitive advantages. At least two major Northwest utilities have been public in expressing their concerns that they would face stranded investments if retail competition develops. Most utilities have expressed concerns about regulatory pressures to undertake conservation, renewable resource development and accommodation of environmental concerns that might raise their rates if their potential competitors – independent power producers, marketers and so on – are not subject to such pressures. They fear such rate increases will mean customers move to other suppliers.

2-B. Restructuring of the Natural Gas Industry

Changes in the natural gas market have been a major factor in the competitive evolution of the electricity industry. In fact, changes in the gas industry may have far more implications for the future of the electricity industry than any other recent development. Not only do low natural gas prices affect future demand for electricity and the cost and characteristics of electricity supply, but the development of a restructured natural gas commodity market may foreshadow similar changes for the electricity market.

In the early 1970s, natural gas was regulated from the wellhead to the end user. Consumers' gas needs were met by their local distribution company, much as electric utilities serve their customers' needs now. The local distribution company had its gas supplies delivered to the city gate by natural gas pipeline companies that acquired the gas supply, transported it to the city gate, and shaped it to meet demand.

Today, pipeline companies do not own or purchase any gas. They provide transportation and shaping services on an unbundled basis. Local distribution companies and many individual customers now purchase their own gas supplies, transportation, and other services as needed. There is now a fully developed natural gas commodity market. Financial instruments, such as natural gas futures, allow local distribution companies and customers to manage the risk of natural gas price fluctuations. A whole new industry of natural gas marketers now exists to help customers acquire gas supplies, transportation and other services on a bundled or separate basis to fit individual customer needs.

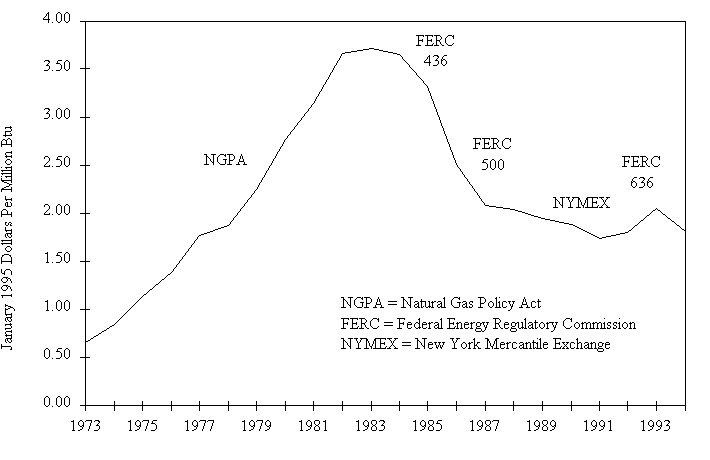

These dramatic changes occurred through a series of restructuring initiatives beginning with the Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978 and culminating in Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Order 636 in April 1992. (See Figure 2-1.) The regulatory changes gradually deregulated natural gas prices at the wellhead (Natural Gas Policy Act, 1978 and Natural Gas Wellhead Decontrol Act, 1989), opened up pipelines for use by anyone wanting to transport gas (FERC Order 436, 1985 and Order 500, 1987), and eliminated the purchase and sale of natural gas by pipeline companies (FERC Order 636, 1992). Order 636 also put into place pricing principles that provided incentives to utilize pipeline capacity more efficiently.

In April 1990, the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) began trading natural gas futures contracts, signaling the beginning of a complete natural gas commodity market. Finally, legislated restrictions on the use of natural gas for electricity generation contained in the Powerplant and Industrial Fuels Use Act were repealed.

Taken together, these changes have put into place the necessary elements for an economically efficient natural gas market. These elements include direct access to markets by both users and suppliers, a larger number of buyers and sellers participating in the market, proper pricing structures in the regulated portions of the industry, and price discovery and risk mitigation mechanisms provided by the spot and futures markets for the natural gas commodity.

The results have been dramatic decreases in natural gas prices and growing estimates of natural gas supply. Between 1983 and 1987, average wellhead real natural gas prices in the United States fell from $3.70 to $2.08 (both in January 1995 dollars), a drop of 44 percent. Since 1987, natural gas prices have averaged $1.89, while displaying price cycles that typify a competitive commodity market. Figure 2-1 illustrates natural gas price trends and restructuring actions over the past 24 years.

Figure 2-1. Restructuring benchmarks and natural gas prices

Until very recently, these lower price levels were considered unsustainable. Such low prices were not expected to garner sufficient new supplies of gas to meet growing demands. However, the establishment of a more competitive market has led to adoption of new technologies that have greatly increased the success, and reduced the cost, of natural gas exploration and development. In only 10 years, the estimates of ultimate potential gas resources have increased five fold. [For an excellent discussion of the changing views on oil and gas supplies see, William L. Fisher, "How Technology has Confounded U. S. Gas Resource Estimators," Oil and Gas Journal , Oct. 24, 1994, pp. 100-107.]

The theories and models of natural gas supply that were developed during the energy crisis of the 1970s and early 1980s have proven to be far too pessimistic. As a new understanding of the nature of natural gas supplies and markets is being developed, forecasts of future natural gas prices have been falling every year for the last dozen years. It is no longer conventional wisdom that natural resource prices will necessarily rise in real terms over time as those resources are produced. This change is reflected in the Council's forecasts of natural gas prices, described in Chapter 5.

Lower gas prices have meant that gas-fired steam generating plants, primarily used by California utilities to meet peaking needs, can now be run economically with gas. These existing generators are already available, they simply have not been used extensively in the past due to the high price of their fuel. The availability of low-cost gas for these plants has meant that the West Coast market has a significant amount of inexpensive electricity at its disposal right now. The extent of that market is described in Chapter 5.

2-C. Gas Turbine Technology

Changes in the structure of the gas industry coincided with improvements in gas-fired power plants. Gas turbine technology has benefited from military and aerospace research and development. This has resulted in improved efficiency and reliability. New gas-fired power plants also are smaller than conventional thermal power plants, so more of their components can be assembled in factories. This makes their onsite construction faster. These two effects combine to reduce their overall costs. In addition, natural gas-fired combined-cycle combustion turbines have greatly reduced local and global environmental impacts. Consequently, they are easier to permit and require less permitting lead time. The dramatic benefits of today's low-cost gas-fired generation and the key characteristics of a gasified coal plant, as described in the 1991 Power Plan, are compared in Table 2-1.

In addition to the direct effect of providing electricity that is inexpensive and less-polluting, the characteristics of gas-fired combustion turbines have also lowered the barriers for entry into the power generation business. It is no longer necessary to undertake the risks associated with very large, long lead time, capital-intensive generating resources to enter the generation business. Thus, one of the conditions for a competitive generation market – ease of market entry – is within reach.

Table 2-1. Marginal Resource Comparison: Draft Plan Compared to 1991 Power Plan

| Resource Characteristics | 1991 Plan Gasified Coal |

Draft Plan Gas-Fired Turbine |

Change |

| Size (MW Capacity of Typical Plant) | 420 | 228 | 46% Smaller |

| Lead Time (years) | 7 | 4 | 43% Shorter |

| Capital Cost ($/kW) | $2,520 | $684 | 73% Lower |

| Availability (%) | 80 | 92 | 15% Greater |

| Efficiency (%) | 36 | 47 | 30% Greater |

| Levelized Cost (cents/kwh) | 6 | 3 | 50% Lower |

| Particulates (T/GWh) | 0.07 | 0.03 | 57% Less |

| SO 2 (T/GWh) | 0.04 | 0.02 | 50% Less |

| NO X (T/GWh) | 0.50 | 0.07 | 85% Less |

| CO (T/GWh) | 0.02 | 0.02 | similar |

| CO 2 (T/GWh) | 985 | 497 | 50% Less |