The Pike Problem

— John Harrison, September 2018 —

Jump to: Invasive species threatens fisheries in Washington | Slowing a runaway species

Eradication partners | Science and pike | Who pays? | An uncertain future

Invasive species threatens fisheries in Washington

Lurking, and apparently thriving, under the quiet, shallow shoreline waters of Lake Roosevelt in Northeastern Washington is an aggressive, invasive predator that has the potential to upset billions of dollars of investment to rebuild native fish populations including redband trout, kokanee, white sturgeon, burbot, and possibly salmon and steelhead.

In response to an emergency that one member of the Northwest Power and Conservation Council likened to a house fire, a pitched battle is being waged in the northern section of the scenic, 151-mile-long lake against the invader, Northern Pike, with gillnets, a no-limit, “catch and kill” fishery, and a reward fishery that pays $10 for each pike head turned in by anglers. Scientific research is also part of the strategy to learn more about the species and how they got in Lake Roosevelt, and how best to control them.

The aim is to beat down the population, protect important fisheries and native fish in the lake, and keep pike from establishing in the Columbia River or tributaries downstream of Chief Joseph Dam, where state and federal fish and wildlife agencies and tribes are working to restore habitat and boost populations of salmon and steelhead, including endangered species.

There is no question the Lake Roosevelt pike population is exploding, or is about to. Hundreds of juvenile pike are stunned during regular electrofishing patrols and scooped from shallow backwaters along the lake shore.

“We knew we had a potential problem when in the fall of 2014 adult pike started appearing in our sampling efforts for juvenile white sturgeon,” said Dr. Brent Nichols, the Fisheries Manager for the Spokane Tribe of Indians. “Then in the spring of 2015 when we started receiving reports of anglers targeting Northern Pike near Kettle Falls, the Lake Roosevelt co-managers met to develop a response plan.” Those co-managers include the Spokane Tribes, the Colville Confederated Tribes, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Huge pike several years old and weighing over 20 pounds have been pulled from the lake with mature kokanee more than 15 inches long in their stomachs. The stomachs of these monster fish also have yielded mice, a bat, and a baby duck. In November 2018 the Spokesman Review newspaper of Spokane reported on the pike problem in Lake Roosevelt, noting that pike have been found just 10 miles from Grand Coulee Dam and that, farther upriver, the Spokane Tribe had caught a true monster pike: 45 inches long weighing 27.5 pounds.

“They’re not afraid to eat,” said Joe Maroney, Director of Fisheries and Water Resources of the Kalispel Tribe in Northeastern Washington. The tribe has successfully controlled a pike population in the Pend Oreille River, which runs beside the reservation. “You have to hit the situation hard, and you have to hit it early.”

“Pike have the ability to eradicate some of our native salmonids that we’re trying to conserve and protect,” said Holly McLellan, a fisheries biologist for the Colville Confederated Tribes. “We’re trying to eliminate pike from Lake Roosevelt, and we’re really concerned about pike spreading through the [Columbia] system.”

Lake Roosevelt is the Columbia River impounded behind Grand Coulee Dam, which has blocked passage of ocean-going – anadromous – salmon and steelhead for some 80 years. More recently, in the 1950s, Chief Joseph Dam, 55 miles downriver from Grand Coulee, also blocked anadromous fish passage.

As the population of Northern Pike in Lake Roosevelt grows – pike were first noticed there in 2011, and the population has been growing ever since – the threat increases to fisheries in the lake that are supported by the Colville and Spokane tribes, and also potentially to fish in the rivers of North Central Washington downstream of Chief Joseph. Those rivers provide spawning habitat for upper Columbia steelhead and Spring Chinook salmon, an endangered species.

Thus, the concern about pike, and the potential impacts, extend beyond the lake and its fisheries, which have financial, recreational, and cultural importance.

Oregon Council member Ted Ferrioli called the pike suppression effort in the lake “an example of an exigency that needs to be responded to,” one that transcends an isolated project to become a regional concern. “This is a house fire,” he said.

Slowing a runaway species

In the race against time and the rapid-fire spawning and expansion of the Northern Pike population in Lake Roosevelt, there is a hopeful example that an aggressive campaign against the predator can be successful.

Northern Pike in the Pend Oreille River, a Columbia River tributary in Northeastern Washington, exploded some 10 years ago but since have been beaten back by the Kalsipel Tribe using the same techniques that the Spokane and Colville Tribes are using in Lake Roosevelt. The Pend Oreille River is the outlet of Lake Pend Oreille and joins the Columbia just north of the border in British Columbia.

Pike apparently established in the reservoir behind Box Canyon Dam in 2004, and numbered an estimated 400 fish by 2006. The population exploded to about 5,500 by 2010. Most other fish species in the river declined. The Tribe began an intensive gillnet fishery to catch as many Northern Pike as possible. That year the tribe caught nearly 6,000. The suppression effort continued with gillnets and reward fisheries for sport anglers, and by the spring of 2017 the Tribe caught only 34 pike. In 2018 the number was 271.

“We were pretty excited,” Kalispel Tribe Fisheries Director Joe Maroney said. “There was a lot of attention given to this where a lot of people in the Columbia Basin thought that we could not do it.”

But they have.

To date, the Kalispel Tribe has removed a total of 18,000 Northern Pike from the Pend Oreille River, nearly all of them in the reservoir behind Box Canyon Dam. The Tribe also is working on pike removal in the next reservoir downriver, the one behind Boundary Dam. There are fewer pike in that reservoir, and gillnetting there appears to have reduced pike abundance by about 80 percent, Maroney said.

In 2018, the Spokane and Colville tribes, co-managers of fisheries in Lake Roosevelt with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, killed approximately 1,600 Northern Pike through gillnetting. Another 435 have been killed by sport anglers through the reward fishery, which is funded by the Colville Tribes. In 2017, anglers turned in 619 heads.

Maroney told the Columbia Basin Bulletin in July that the sharp decline in the Pend Oreille River pike population over a five-year period shows the effectiveness of intensive gill netting, which has been gradually reduced to match the declining catch.

He also has been thinking about the potential economic impact of a pike invasion into the Columbia River Basin, including Lake Roosevelt. Using a model developed in California to assess the impact of a pike invasion in Lake Davis northeast of Sacramento, Maroney estimated the impact at $33 million for Washington alone, a figure he called “crude” because he made assumptions to get a general idea. He titled a Northern Pike presentation he gave to a March 2018 meeting of the Washington Salmon Recovery Funding Board, “You should be afraid … Be Very Afraid.”

And there is another concern with pike, one that could menace sport anglers: chemical contamination. In July 2012, the Washington State Department of Health issued an advisory for Pend Oreille River pike consumption, warning people not to eat pike over 24 inches long because the fish accumulate mercury in their flesh, and by the time a pike has reached that length its mercury concentration is dangerous. Pike under 24 inches can be consumed, but the Department advises only two meals per month.

What about pike in Lake Roosevelt?

Holly McLelllan, principal fisheries biologist for the Colville Confederated Tribes, said tissue samples were collected in July from pike in Lake Roosevelt for analysis by the Environmental Protection Agency. “We expect a fish-consumption advisory by the end of the year,” she said.

Eradication partners

A small army has been raised to fight the presence of Northern Pike in Lake Roosevelt, including the state of Washington, the Spokane and Colville tribes, and the three mid-Columbia public utility districts that own five dams on the Columbia River downstream of Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams.

The Douglas County Public Utility District, which owns and operates Wells Dam, the first downriver from Chief Joseph, is watching the pike suppression effort carefully.

While Douglas is not contributing to the current suppression effort, “we stand ready to fund suppression efforts in Wells, should pike be identified in that section of the Columbia River,” utility spokeswoman Meaghan Vibbert said.

“Pike are on our radar for sure,” said Steve Hemstrom, a senior fisheries biologist for the Chelan County Public Utility District in Wenatchee, which owns and operates Rocky Reach and Rock Island dams, the second and third dams downriver from Chief Joseph.

Bill Towey, a fisheries scientist for the PUD, said the utility is very concerned about the Northern Pike presence in Lake Roosevelt and the Columbia River Basin and supports the continued suppression and early detection efforts.

Hemstrom said he’s confident pike will be detected in the fish-passage facilities at the Rocky Reach and Rock Island dams if they entrain over Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph. So far, none has been detected.

While that could change, Hemstrom thinks it is unlikely. Water flows past and through the two dams more quickly than in slow-moving Lake Roosevelt, and the Columbia near Wenatchee has fewer shallow backwater areas pike prefer. Thus, salmon and steelhead smolts move through the area quickly, perhaps too fast for pike.

“We know that pike are not chase predators; they are burst-and-ambush predators,” he said. “So would they prey on salmon that are moving quickly? Probably not. Do the migrating salmon go into backwater places where pike like to hide? Probably not.”

Tom Dresser, of the Grant County Public Utility District, which owns and operates Wanapum and Priest Rapids dams on the Columbia, the fourth and fifth dams downriver from Chief Joseph, said the utility is keeping a close lookout for pike.

“Grant PUD has crews on the water from mid-March through October of each year, five days per week (Monday-Friday),” Dresser said. “If pike were detected, crews can be redirected within a matter of hours to that location to employ suppression and removal efforts. I believe that Grant PUD is in a good position to detect and respond if necessary.”

The experiences of pike investigations in Canada might give some pause, however. Canadian researchers found pike are extremely adaptable and able to easily survive along rocky shorelines and in fast-moving rivers, not only in their preferred habitat of shallow lake and river waters. If there is a likely spot where pike might take hold downstream of Chief Joseph, a sort of point of first contact, a wide spot along the north shore of the river called Lake Pateros, after the adjacent city, Pateros, is a good candidate. Biologists are watching it carefully. The habitat there is similar to the areas around the mouths of the Kettle and Colville rivers in Lake Roosevelt that pike prefer.

Salmon and steelhead spawn in Columbia River tributaries, and those fish might be affected by pike if they get below Chief Joseph, a potential the Chelan PUD recognizes.

“We’re still evaluating this,” Hemstrom said.

The Council has a web-based tool, here, that provides current Northern Pike suppression data, information on the treats the predator poses, and information about how the public can help keep pike from reaching anadromous waters below Chief Joseph Dam.

But the Columbia below Chief Joseph Dam also has what might prove to be a secret weapon against pike, he said: Stickleback, a carnivorous fish that don’t grow very large – about four inches long at best – but have a broad appetite that includes insects, small crustaceans, and fish larvae.

“Stickleback are predators on pike eggs, and we have gobs of stickleback,” Hemstrom said. “Even if pike could spawn in these areas, the sticklebacks would eat them, most likely.”

One complication of the pike suppression effort, potentially at least, is that there is no coordinated plan of attack if pike take hold downstream of Chief Joseph. Washington’s Invasive Species Council is working to change that by, for example, proposing the creation of a state emergency-response fund and facilitating the development of a plan for how to respond to the continued spread of Northern Pike.

“We need a plan as well as funding,” the Council’s executive coordinator, Justin Bush, said. “In terms of invasive species, Northern Pike is one of our highest priorities. “Some species, we know, would be more damaging to our infrastructure and natural resources, like zebra and quagga mussels, but they are not currently here.”

Zebra and quagga mussels form hard masses of finger nail-sized shells that can clog water intakes and other submerged structures such as equipment at dams. They have infested areas of the Midwest and Southwest, but so far not the Northwest.

Greer Meier, Science Program Manager for the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board in Wenatchee, said the board is tracking and participating in pike-suppression forums, as well as staying in contact with the public utility districts as they watch for pike.

“Our Upper Columbia listed salmon and steelhead could face a major threat from these fish moving downstream and occupying the reservoir areas where juveniles are migrating and rearing,” she said.

The Western Governors’ Association has identified Northern Pike as one of the top threats in the West and established the Biosecurity and Invasive Species Initiative to focus attention on the impacts that invasive animals, plants, pests, and pathogens have on ecosystems, forests, rangelands, watersheds, and infrastructure in the Western United States. Workshops on challenges and opportunities in addressing invasive species are planned, and the Initiative could help coordinate a rapid response or leverage federal funding in the future to fight the problem.

Elsewhere, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe of Indians also is working to eliminate Northern Pike from parts of Lake Coeur d’Alene, where the species was introduced illegally. In a letter to the region in August 2018, Caj Matheson, director of the Tribe’s Natural Resources Department, wrote that targeted suppression efforts to remove pike from Windy Bay to protect native Westslope Cutthroat Trout and Bull Trout have been promising and that the Tribe plans to expand suppression efforts beyond Windy Bay with a “large-scale suppression effort” in 2019.

Angelo Vitale, fisheries program manager for the Tribe, said there have been “some very positive responses to this early work,” adding, “the Tribe is committed to redoubling its effort to implement a large scale suppression strategy to bolster the production of culturally important species like westslope cutthroat trout and bull trout.”

He said the strategy is well aligned with the mission of the Tribes to promote the recovery of native fisheries for the benefit of future generations. It also seems to be well aligned with the interests of the angling community, he added.

“Notably, the responses by anglers to a 2017 survey indicated broad support for both native species conservation efforts as well as for management strategies that aim to reduce the negative impacts of Northern Pike on more desirable fisheries," Vitale said.

Science and pike

In a reservoir the size of Lake Roosevelt, it is critical to be able to pinpoint the pike hotspots and fish for them there. Picking the places to set nets is not random guesswork.

“We have a shape file of the reservoir that shows where the areas of shallow water are, less than 25 feet,” said Holly McLellan, chief fisheries biologist for the Confederate Colville Tribes. “They like shallow water. We try different areas, and if we get a lot of fish we will stay there, and if not we move on.”

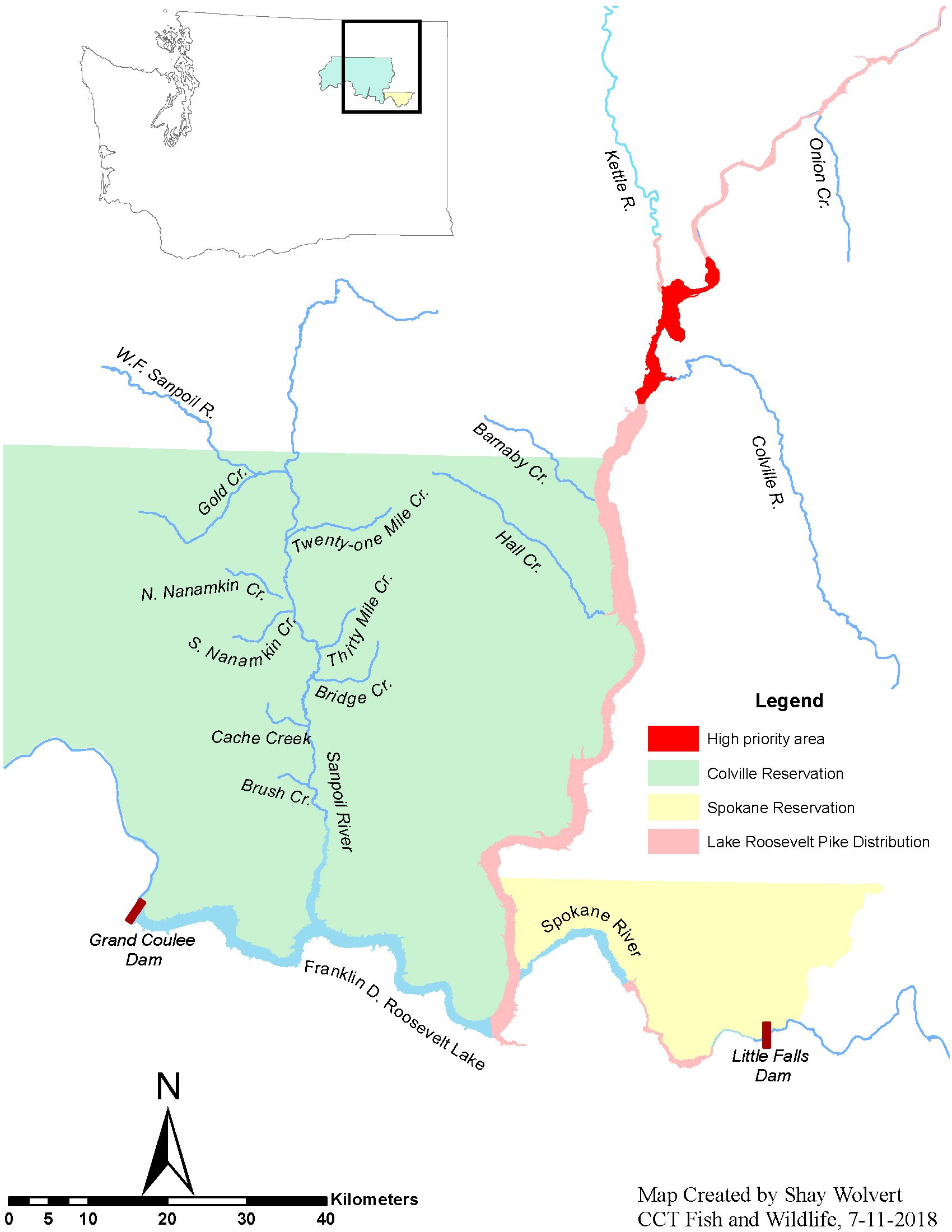

The mouth of the Colville River has been a pike hot spot, partly because pike prey on juvenile burbot and the Colville produces a lot of burbot. When pike spawn they tend to move out of that area and go across the river and upstream to the mouth of the Kettle River, another pike hotspot, McLellan said.

While it isn’t clear how pike got into Lake Roosevelt in the first place, microchemistry analysis might help unlock that mystery. It is known that pike invaded some lakes and rivers in Montana, including several that are in the Columbia River Basin, some time ago, and subsequently were found in the Pend Oreille and Columbia rivers.

So pike could have migrated downriver into Lake Roosevelt from the Pend Oreille, or they could have come from British Columbia, where pike also have been found in the Columbia River. Or they could have come from the Spokane River, or they could have come from who knows where in buckets and dumped in the lake.

The Spokane flows from Lake Coeur d’Alene, and biologists are concerned the lake could be feeding pike into the Spokane River and Lake Roosevelt. As a result, biologists have been watching the Spokane River closely. Pike are occasionally observed in the riverine section of the Spokane River from the Washington state line downstream to Nine Mile Dam. Between Nine Mile Dam and Long Lake Dam, referred to as Lake Spokane, a robust Northern Pike population exists. Little attention has been given to this population due to a lack of funding. However, fishery managers realize it could be a possible source of pike in Lake Roosevelt. In 2017 and 2018, biologists collected at least five Northern Pike from the Spokane Arm of Lake Roosevelt.

Meanwhile Dr. Kellie Carim, a scientist with the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula, Montana performed genetic analysis to understand the distribution of pike in the Columbia River Basin and to identify the original source populations that led to the invasion in eastern Washington.

Dr. Carim collaborated with the Colville Confederated Tribes to collect environmental DNA (eDNA) samples in in the Fall of 2017 and the Spring of 2018 from Lake Roosevelt and some of its tributaries (the Kettle, Colville, Sanpoil, and Spokane rivers, and Wilmont and Hawk creeks, which are near the mouth of the Spokane River). Environmental DNA is DNA from an organism that is sloughed off and left behind in the surrounding environment. By collecting water samples, biologists detect an animal simply by looking for its DNA in the water sample. The eDNA samples showed positive detections of pike from the upper part of Lake Roosevelt down to Wilmont Creek, as well as in lower reaches of the Spokane River. This distribution is consistent with previous reports of live pike in these areas of Lake Roosevelt. To better understand any changes in the distribution of pike in Lake Roosevelt, Dr. Carim and the Colville Confederated Tribes will continue to collect eDNA samples in both the spring and the fall. This will allow them to quickly identify any further spread of pike in Lake Roosevelt. Changes in pike presence between spring and fall samples will also provide information on where pike tend to reside during the spawning and growing seasons.

To understand the original source of pike in recently invaded areas of the Pend Oreille River and Lake Roosevelt, Dr. Carim compared the genetic makeup of fish in these areas to other potential source populations in the Coeur d’ Alene River and Clark Fork River drainages in Idaho and Montana. Although established pike populations in the Clark Fork River drainage (including Lake Pend Oreille) are closest geographically to the newly invaded areas in the Pend Oreille River of eastern Washington, genetic analysis suggested that fish from the Clark Fork River drainage are not the source of fish in recently invaded areas of eastern Washington. Instead, many pike in the Pend Oreille River and Lake Roosevelt are most genetically similar to pike in Medicine and Cave Lakes, two small lakes located upstream of Lake Coeur d’Alene in Idaho. These data suggest that fish arrived in the Pend Oreille River by illegal human transport because there is no direct water connection between lakes Coeur d’Alene and Pend Oreille. However, there are some pike in the Pend Oreille River and Lake Roosevelt that are not related to any of the established pike populations in the current database. This suggests that fish may have also been introduced to eastern Washington from additional populations outside the Clark Fork and Coeur d’Alene River drainages.

Chemistry also is an important tool in the search for the origins of Lake Roosevelt pike. Scientists for the Colville Tribes are testing chemical elements in the water of Lake Roosevelt and its tributaries and comparing the elements with those found in the ear bones, or otoliths, of pike, where the elements accumulate as the fish grows. In particular, researchers look for strontium. Each stream has a unique strontium isotope signature.

“So if you look at the otolith and analyze from the center out, the strontium signature changes over time if the fish moves into different bodies of water,” McLellan said. “We have cataloged most of the major bodies of water in the area. We are then able to match the water and otolith signatures. This is how we can tell which body of water a pike originated from and where it moved from one system to another. For example, the Kettle River has a much lower strontium signature than Lake Roosevelt. So we were able to verify that Northern Pike were spawning in the Kettle River, and then migrating out of the Kettle River into Lake Roosevelt to rear.”

To date, the tribes have identified spawning areas in the Kettle and Colville rivers and in Lake Roosevelt near the community of Evans north of Kettle Falls. Pike from Lake Roosevelt will be tested to determine if they came from the Pend Oreille River and pike from the Spokane River will be tested to determine if they came from Coeur d’Alene Lake. This information will help the Spokane and Colville tribes focus suppression efforts in the proper locations.

Considering only the fish in eastern Washington, many of the pike in Lake Roosevelt are most closely related to those immediately upstream in the Pend Oreille River. These data suggest that after fish were introduced into the Pend Oreille River, they spread downstream into Lake Roosevelt. Biologists with the Colville and Spokane Tribes have documented active reproduction of pike in Lake Roosevelt. Consequently, Lake Roosevelt is being populated by both natural reproduction within the watershed and immigration from upstream waterbodies.

Illegal human introductions of pike have occurred in Idaho and Montana since the 1950s, and continue today. Dr. Carim and the Colville Confederated Tribes have identified a few established pike populations that are the likely source of illegal introductions to eastern Washington. However, the data also suggest that additional populations need to be considered in this research. Dr. Carim is seeking funding and partnerships with collaborators to collect samples from additional established pike populations in Montana, Idaho, and Canada. Information from additional established pike populations will help biologists understand how pike have moved both naturally and with human assistance throughout the Columbia River Basin.

Scientific research also is focusing on the type of gear used to catch pike.

“Gill net material, dimensions, construction, and deployment strategy all influence fish catch rates,” said Elliott Kittel, a fisheries scientist with the Spokane Tribe of Indians. “With the Colville Tribes we are jointly experimenting with several types of nets to maximize pike catch and minimize bycatch.”

The tribes have been experimenting with two different net materials, a monofilament net in different mesh sizes and made of the same clear material used by commercial fishers to catch salmon in the lower Columbia, and a multifilament net that is constructed of braided nylon. In Lake Roosevelt, the monofilament nets have the drawback of “catching a lot of fish we’re not targeting, including walleye,” a popular recreational fish, McLellan said.

“The white sturgeon researchers in Lake Roosevelt use the braided nylon nets and noticed that their only bycatch was Northern Pike, and we thought that was really interesting,” McLellan said. “So we thought we would experiment with it, too.”

Preliminary catch data is promising, with high Northern Pike catch rates and low bycatch of non-targeted fish in the braided nets, McLellan said.

The Colville Tribes have been experimenting with two-inch stretch mesh, and the Spokane Tribe is experimenting with several other mesh sizes. At the end of the year, the agencies will combine their datasets and use the information to select nets that are efficient in Lake Roosevelt. However, each body of water is different, and what works well in one may not work very well in another. For example, the Kalispel Tribe experimented with braided nylon nets, but they were not effective because the Pend Oreille system has lots of Yellow Perch that filled their nets. Agencies need to learn from other agencies and adapt strategies that will work best in their waters, McLellan said.

Who pays?

Funding for the pike suppression effort in Lake Roosevelt comes from a joint commitment of the tribes, Bonneville Power Administration, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and others including the Chelan and Grant public utility districts, which own a total of four dams on the Columbia. It is a requirement of the PUDs’ federal licenses to operate the dams that they fund projects to improve habitat and dam-passage for fish, particularly salmon and steelhead, and wildlife that are affected by the dams. Pike potentially threaten those investments.

While the Chelan PUD provided $50,000 last year toward the Lake Roosevelt effort, the Colville Tribe $35,000, and WDFW $15,000, funding has come primarily from the Bonneville Power Administration, although in 2018 the Colville and Spokane tribes augmented the Bonneville money with some of their own funding, and the Grant County Public Utility District committed $75,000 for the three-year, 2017-2019 period. In 2018, the two tribes submitted a proposal to the Council for Bonneville funding for the next three fiscal years, 2019-2022, for about $4.5 million, or about $900,000 a year, with a commitment to seek additional funds from other entities including the state of Washington, federal agencies, and the three mid-Columbia Public utility districts.

The commitment to seek additional sources of funding besides from Bonneville resonated with the Council members. At its June 2018 meeting, the Council unanimously recommended the project to Bonneville for funding.

“There is a need for seed money for this [pike suppression] project, and one thing I like about it is that the partners are aggressively seeking other, permanent, funding so it won’t just be from Bonneville,” Idaho member Bill Booth said. Guy Norman, a Washington member of the Council and chair of the Council’s Fish and Wildlife Committee, agreed, adding he was pleased that “the partners are focused on reducing the threat to Lake Roosevelt, and also to anadromous fish downstream.”

In June, the Spokane Tribe was notified it had received a second round of funding totaling $144,000 from the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and in late August McLellan learned the Colville Tribes will receive a $104,000 grant from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“The money is for one year, through September 2019, and I will need to re-apply next summer,” she said. “These funds, combined with our Bonneville Power funds, now gives me enough security to hire a new biologist to help me run this project.”

In September, the Council approved a request from the Spokane Tribe and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and recommended that Bonneville direct $301,473 of cost savings from other projects to the pike suppression project in 2019.

Helping to support the various funding proposals and requests, the suppression project is supported by the Council’s Independent Scientific Review Panel (ISRP). According to a memo prepared by the Council’s Fish and Wildlife Division staff, the ISRP reported that the proposal met the criteria for a short-term suppression effort “that could quickly and significantly change the abundance of Northern Pike and provide additional information regarding the status of the species in the Upper Columbia Basin.” The panel included specific qualifications intended to strengthen the proposal in light of what the memo called the “urgent need to get a better understanding of the control and suppression of Northern Pike in Lake Roosevelt.”

An uncertain future

It’s hard to be optimistic about a problem that has such explosive potential to impact fisheries throughout the Columbia River system.

From what seemed like a harmless fish that’s fun to catch, the specter of monster in our midst has grown.

“We view pike as a problem, not as a fishery,” said Chris Donley, Region 1 Fish Program Manager for the Washington Department of Wildlife in Spokane. The department’s policy regarding pike is simple: If you catch one, you can’t release it live. You have to kill it.” The Department maintains a website on Northern Pike, here.

“Science is a learning process,” said Justin Bush, executive coordinator of Washington’s Invasive Species Council, a division of the state’s Recreation and Conservation Office. “In Washington Northern Pike was a game fish until 2011, and now it is a prohibited, aquatic invasive species. When we realized the impacts, the classification was changed. We see this as an imminent threat, and we are worried about it economically as well as biologically.”

He said pike threaten tribal, commercial, and sport fisheries and, if they establish downriver of Chief Joseph Dam, pike threaten the state’s substantial funding of salmon recovery efforts. Since 1999, the Washington State Salmon Recovery Board has directed $731 million for work to, primarily, improve salmon habitat, he said.

“In my observation, the pike situation in Lake Roosevelt is a growing concern,” said Elliott Kittel, a fisheries biologist for the Spokane Tribe, said. “We have only very recently been able to reorganize internal funds toward pike suppression. Dedicated funding will be required to adequately combat pike population growth and expansion.”

The fish, and the problem, could be migrating ever closer to the anadromous zone below Chief Joseph Dam.

“We are finding pike farther south in Lake Roosevelt with more regularity than ever before,” Kittel said. “Pike abundance appears to be increasing in the Kettle Falls area, as well. The first pike was collected in the Spokane River Arm of Lake Roosevelt at the end of 2017, and more have been collected since.”

Holly McLellan, principal biologist for the Colville Confederated Tribes, said the tribes hypothesize that pike are moving down the reservoir at the rate of about 50 kilometers, or 31 miles, per year.

The mouth of the Kettle River is 109 miles from Grand Coulee Dam; the mouth of the Colville River is 100 miles. Both are infested with pike. The mouth of the Spokane River is 43 miles from Grand Coulee, and recently an angler caught a pike in Hawk Creek, which is downstream from the mouth of the Spokane River and just 31 miles above the dam.

They eat anything in their path and they threaten important fisheries in Lake Roosevelt and potentially salmon and steelhead downstream in the Columbia River. The state’s TVW channel produced a special program about the pike invasion. Watch it here.