Sockeye: Ups, Downs, and Optimism Amid a Downturn

— John Harrison, August 2019 —

Sockeye salmon runs are cyclic, a fact of nature that is evident this year in the run size forecast for the Columbia River, which recently was reduced. If the run is up one year, it likely will be down the next. While that is not unusual, here is something that is: these summer-migrating fish appear to be adapting their timing to a warmer river, with the run peaking earlier today than in the past, and despite the challenges of crossing nine Columbia River dams on their journey to the ocean and back, the largest component of the Columbia River sockeye run, those from the Okanagan River, is thriving.

More than other species of salmon, those that migrate in the summer – sockeye, summer and fall Chinook, some coho – face the daunting impacts of climate change, which portend warmer rivers and altered flow patterns. Fishery managers and fish scientists are watching these runs carefully, and the most affected of all the summer-run fish may be sockeye.

The sockeye run in the Columbia comprises three distinct populations – those that spawn in the Wenatchee, Okanagan, and Snake river basins. The 2019 run initially was estimated at 94,400 fish late last year, but was downgraded in July to 62,800. The vast majority of those fish return to the Okanagan River, the second-largest component returns to the Wenatchee River, and the smallest component returns to the Snake River Basin, where the fish are listed as an endangered species. The initial 2019 forecast for the Snake River fish was 129 crossing Lower Granite Dam, but by late July only 25 had been counted there. By the same date, the total number of sockeye counted at Bonneville Dam was 62,115.

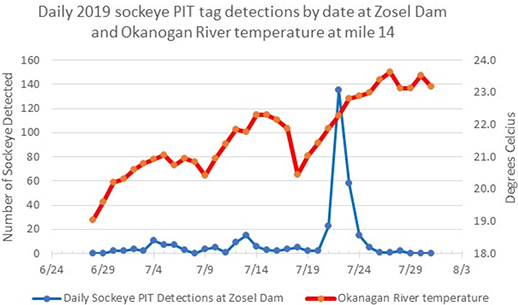

The Okanagan run migrates through a river that is notoriously warm and shallow in the summer, from its confluence with the Columbia just downstream from Chief Joseph Dam, north into its headwaters lakes in Washington and British Columbia. Historically, the sockeye run peaked in early July, but over the past 30 years or so the peak has steadily moved earlier, by about 11 days, now peaking in late June when the water is a little cooler. This earlier migration has consistently resulted in higher fish survival into British Columbia in recent years.

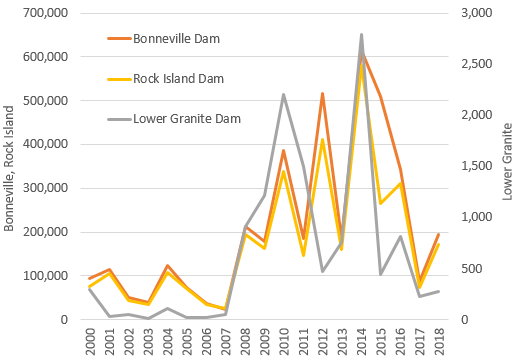

Conclusions are best made by observing long-term trends, as sockeye returns always have a kind of roller coaster trend year to year. For example, the 2014 run, the largest sockeye run since fish counting began at Bonneville Dam in 1938, saw more than 600,000 fish counted at Bonneville, the first location fish can be counted on the Columbia when they return from the ocean. The previous year, 2013, the run was about 185,500. In 2015 the Bonneville count was more than 500,000, but about half of those fish died before reaching McNary Dam 146 miles upriver because the river was unusually warm and runoff unusually low that year.

Considering that the total 2018 run was 193,816, a downturn for this year was not unexpected. While the July forecast is about 134,000 less than the 2018 return, based on long-term historic trends a decline of 65 percent year over year, like 2018-19, is large but may not be unusual.

Still, what happened?

Warm river, poor ocean

No doubt, the 2019 decline is partly attributable to the impact of the disastrous return of 2015 that killed so many adult fish. The diminished run that survived to spawn produced fewer juveniles than in most recent years, and their downstream journey to the ocean may have been confounded by predation and poor feeding conditions once they arrived in salt water. The warm-water phenomenon in the north Pacific known as The Blob for its appearance on maps of sea-surface temperatures, also is believed to have contributed. The Blob was in place from 2013 until dissipating last year.

The warm water caused a decline in food organisms for salmon and probably contributed to the decline of sockeye and Chinook salmon, and to poor returns this year. The 2019 return of spring Chinook to the Columbia was the lowest on record, and the poor returns continued into the summer, when Washington state suspended summer Chinook fishing. The problem also affected Canadian salmon, where officials blamed The Bob for killing juvenile sockeye that entered the ocean in 2013 and later. British Columbia closed the recreational sockeye fishery on the Skeena River in the northern part of the province. The return of sockeye and pink salmon to the Fraser River also may be affected. An update issued by the province on July 9 read, in part: "[The Department of Fisheries and Oceans] has advised that Fraser River sockeye salmon forecasts for 2019 continue to be highly uncertain due to variability in annual survival rates and uncertainty about changes in their productivity as a result of changing ocean conditions from 2013 to 2018 that included the warm blob and an El Nino event.”

In Washington, the Department of Fish and Wildlife is watching the summer salmon returns carefully. “In this case, 2019, the sockeye counts have been tracking well below where we would have expected them to be if the run size were equal to the forecast,” said Bill Tweit, Columbia River coordinator for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. “The cause of the lower-than-forecast run size is not known with certainty, but it is likely that marine survival was lower than we had estimated it would be.”

Annual run-size estimates are a work in progress and are adjusted as fish are counted at Bonneville. For 2019, while initial estimates of run sizes were made late last year based on historic trends, the U.S. v. Oregon Technical Advisory Committee (TAC), which consists of federal, state, and tribal fish managers, downgraded run-size estimates for sockeye in July. This is important because based on the estimates, the TAC determines how many fish can be allocated for harvest and how many should be allowed to escape harvest to spawn, and then using this information the states of Washington and Oregon set fishing seasons. The 2019 sockeye run was disappointing, particularly for the Snake River run. Only 17 adult fish returned to the Stanley Basin, 900 miles from the ocean; the 2018 return was 276. A total of 730,000 hatchery-reared sockeye smolts were released in Idaho in 2017, and the returning adults in 2019 came from that release. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game will continue to rely on two hatcheries to keep the run going while the effort continues to restore a naturally spawning population. This fall, 610 adult sockeye were released into Stanley Basin lakes to spawn naturally.

The 2020 sockeye run, Okanagan, Wenatchee, and Snake combined, may be large again, as this year the number of fish – males and females – that return after one year in the ocean rather than the typical two years – was high in the Okanagan as a percentage of the overall run. “We haven’t had such a high percentage since the early 1990s,” said Dr. Jeffrey Fryer, a biologist at the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) who studied Columbia River sockeye for his Ph.D. dissertation. He has followed sockeye for CRITFC for some 30 years. “This looks like one of the highest number [of early-returners] since we started sampling at Bonneville in 1985, and all four of the highest returns have been since 2011.” A high number of early returners in one year usually means a high number of two-ocean fish the following year which, on average, comprise about 80 percent of the run. (This year, two-ocean sockeye at Bonneville comprise only about 30 percent of the run while the early-returners comprise almost 50 percent).

But again, observing long-term trends, sockeye returns to the Columbia began a steady upward climb in 2007 that lasted seven years, and since then the trend has been generally down.

Why?

While there is no single answer for the downturn this year and since 2007, there are several possibilities. Ocean conditions are one; summer water temperatures likely are another. Warm summers since 2007 combined with periodic temperature shifts in the ocean as El Nino and La Nina conditions waxed and waned wreaked havoc on salmon and other species as they reached the ocean as juveniles and later returned as adults.

As summer migrants, adult sockeye are uniquely susceptible to rapid variations in water temperature, and if the water is too warm fish can die, as happened in 2015. That summer, 510,706 sockeye were counted at Bonneville, and just 279,744 were counted at McNary, meaning that almost a quarter million were lost. Most died in the river, and others turned off into tributaries seeking cooler water. Most of those ultimately died, too. It was a disaster, not only for sockeye but also for other fish, including sturgeon and summer Chinook.

Reason for optimism

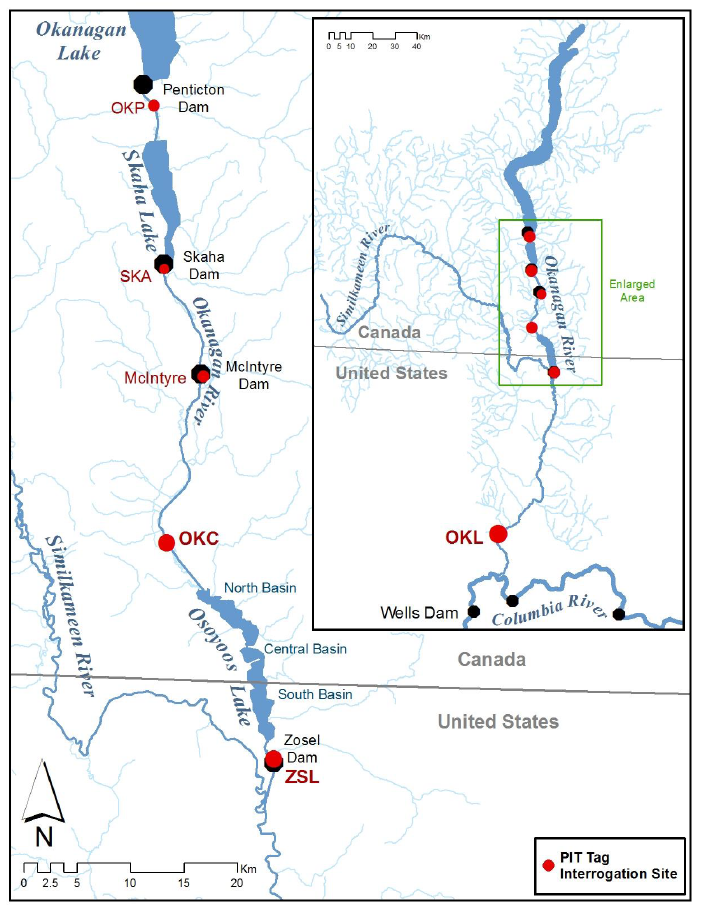

Dr. Fryer noted water temperature and ocean conditions as factors but is hopeful about other trends that portend better returns in the future. Spawning and rearing habitat in the Okanagan River and in the headwaters lakes is steadily being improved. Much of the credit for that goes to the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA), a First Nation in British Columbia that has been working to improve sockeye dam passage, habitat, and natural production in the Okanagan River and its tributaries. The improvements include channel restoration and construction of spawning beds, and better access to spawning habitat as the result of fish passage improvements at two dams – McIntyre and Skaha in British Columbia.

Additionally, the ONA has a sockeye hatchery in Penticton to spur sockeye restoration in Skaha Lake and for juvenile fish releases into Okanagan Lake. The hatchery is funded by the Grant and Chelan public utility districts as part of their effort to mitigate the impacts of the four dams they own on the Columbia. These returns currently comprise about 10 percent of the run. A goal of the ONA is to see fish pass over Penticton Dam, 664 miles from the ocean, which would open up 84-mile long Okanagan Lake to sockeye production for the first time since the early 1900s.

Another reason for increased escapements is reduced harvest levels due to efforts to protect ESA-listed Snake River sockeye. The Columbia sockeye run used to be managed for an escapement of about 25,000 on the Okanagan River spawning grounds with harvest allowed of any “surplus.” An escapement of only 25,000 arguably could not produce a return (to Bonneville) of 500,000 as happened in 2015. Based on the large escapements in recent years, biologist Dr. Kim Hyatt of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada estimates a more appropriate escapement goal is more than 100,000 sockeye for Osoyoos Lake alone. The international border passes through the lake.

Fryer noted a model funded by the Douglas County Public Utility District, which owns and operates Wells Dam, the last Columbia River dam Okanagan sockeye cross on their journey to spawn (there are dams on the Okanagan River, too), is improving management of Okanagan River flows to balance competing interests for water such as agriculture, flood control, recreation, the needs of resident kokanee, and sockeye. The Grant and Chelan public utility districts, in addition to the Bonneville Power Administration, have helped fund juvenile and adult monitoring programs that provide data used in the model to better manage Okanagan sockeye. Bonneville funding comes from a Columbia Fish Accords project with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission.

Despite the steady decline since 2007, the future looks hopeful as habitat and passage improvements continue, as water management in the Okanagan improves, and as the fish shift their run timing in response to a warming river. Fryer said elders of the Okanagan Nation recall that sockeye historically consisted of two runs, one in July and the other in May (the latter possibly bound for Okanagan Lake), and so perhaps the earlier run may be re-establishing.

But there always is the unexpected, such as the weather. Hot weather in June this year warmed the Okanagan River, stopping sockeye migration when few fish had passed Wells Dam. However, in late June through the middle of July the weather cooled, resulting in a high rate of passage into Osoyoos Lake for the early-migrating run. Now, as the peak of the run passes Wells Dam, temperatures have been warming, and that likely will set up a thermal barrier in the Okanagan River. The question is whether this barrier stays until late August or even September, requiring sockeye to hold in the pool behind Wells Dam with higher mortality than if they made it to Osoyoos Lake.

Or, Dr. Fryer said, will there be a dip in temperature that is large enough and long enough for sockeye to make a run up to the North Basin of Osoyoos Lake. (The southern and central basins of Osoyoos Lake are warm and shallow, offering no habitat for holding until spawning.) Or also, he added, “will the sockeye be lured up the Okanagan River by a short dip in temperatures, only to have an increase in temperature snap the trap shut before they make it to the North Basin resulting in high mortality, as happened in 2015 several times and has been observed in several other years as well.” He said these are the risks faced by the Okanagan fish every year.

“The reward, if they make it, is a much-improved spawning habitat in perhaps the most productive sockeye lake for its size in the world,” Dr. Fryer said.

As a sockeye expert, Dr. Fryer said the Okanagan run is amazing to watch.

“Every year they run a gauntlet of nine mainstem dams plus two or three Okanagan River dams on both upstream and downstream migrations with adults facing extremely high temperatures as well. Yet this run has not only persisted but thrived,” he said. “This time of year, I’m frequently looking at dam counts, temperature data, and PIT tag detections to try to figure out how the run is responding to the hostile conditions that Mother Nature throws at it. And nearly every year, enough of the returning adults figure out a way to beat the high temperatures and survive to spawn to keep this run not only persisting, but thriving. No other sockeye stock in the world could survive the temperatures faced by this stock. It is truly amazing to see.”