The Council's Independent Economic Analysis Board (IEAB) has served as the technical reviewer of the economic analysis for the Corps of Engineers' Lower Snake River Juvenile Salmon Migration Feasibility Study. This analysis is often referenced by the acronym of the group that accomplished and advised the analysis — DREW, for Drawdown Regional Economic Workgroup.

As technical reviewer, the IEAB has been involved in review of that work as it has progressed over the last few years. The IEAB has commented on the project study plan, preliminary work group reports, a preliminary draft economic appendix, and most recently on the draft Economic Appendix I (see above link).

The IEAB's intention throughout this review process has been to help make the economic analysis a more useful and reliable source of information for regional decision-makers. The DREW and the Corps have responded positively to IEAB comments in most cases, and we believe that the IEAB's comments and suggestions have significantly improved the economic analysis.

The purpose of this memorandum is two-fold: to inform the Council about the IEAB's comments on the draft economic appendix, and to briefly summarize the findings of the economic analysis. It is hoped this level of detail will be useful to the Council as it amends its Fish and Wildlife Program.

The IEAB's general assessment of the presentation and analysis in the draft economic appendix is that it is of a balanced professional quality. However, there are several weaknesses remaining. Some of these can be addressed in the final report, but some will remain because of limited information on which to base estimates.

The IEAB comments included 33 pages of detail. The full text of our review comments is presently available on the Council's web page under the IEAB. Below we summarize the finding of the economic appendix and discuss some of the most significant issues raised in our review comments.

We want to be clear that some estimates in the economic appendix are woefully imprecise, especially the estimated benefits of recreation and estimated passive use values for salmon and rivers under the dam-breaching alternative. Without additional work to reduce the range of uncertainty in these estimates, the overall economic assessment cannot be considered conclusive regarding choice among the alternatives evaluated. The primary reasons for this are: First, the biological effects remain highly uncertain for all of the reasons the Council is familiar with. Second, economic benefits associated with non-market activities like recreation are difficult to measure and theestimates range widely depending upon assumptions. Finally, the estimated tribal benefits from salmon runs and the natural environment, and future environmental and treaty requirements, are uncertain enough to render the analysis inconclusive.

Below we discuss the costs and benefits of the four alternatives considered in the economic appendix; (1) existing conditions, (2) maximum transport of smolts, (3) major system improvements, and (4) dam breaching. Alternative 4 had both the largest costs and largest benefits. According to the PATH analysis, all four alternatives met, or came very close to meeting, 24 and 100-year survival standards. However, only alternative 4, breaching, met the 48-year recovery standard. The economic appendix reports that more recent PATH modeling shows that the non-breaching alternatives were able to meet the recovery standard, although they are considered less robust than the dam breaching alternative.

The economic appendix reports the net costs (costs less benefits) of alternatives 2 and 3 to be small negative numbers. That is, alternatives 2 and 3 are expected to yield small net economic benefits. The net cost of alternative 4, dam breaching, however, is estimated to be $246 million per year more than current conditions. These results are based on an assumed discount rate of 6.875 percent. Using the Council's 4.75 percent discount rate, the net cost of alternative 4 is calculated to be $216 million per year. Below we look at the costs and benefits of dam breaching separately using the 4.75 percent discount rate (without necessarily endorsing that particular rate as being appropriate for economic analysis).

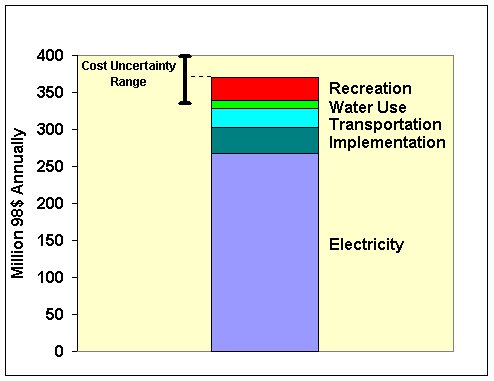

We begin with costs. Figure 1 shows the components of the cost estimated for the dam breaching alternative. It also shows what the range of uncertainty is around the medium estimates. Each of the cost components is described below along with a characterization of the IEAB's comments. Because alternatives 2 and 3 have only small economic effects, our discussion focuses on the effects of alternative 4, dam breaching.

The total costs of dam breaching amount to $370 million per year. The uncertainty of the cost estimate resulted in a range from $343 million to $400 million, or about plus or minus 8 percent. This is illustrated by the black line to the left of the cost bar in Figure 1. It is clear from Figure 1 that lost hydroelectricity production accounts for the bulk of the costs of dam breaching.

Figure 1. Costs of Alternative 4: Breaching Lower Snake Dams

Electricity — Effects on electricity generation are the largest cost item by far of alternative 4. Given existing modeling tools, the energy lost due to breaching is well understood and the uncertainty range is relatively small. On the other hand, the probable changes in the costs of transmission, peaking capacity and ancillary services are much less well understood and the IEAB has raised some questions in this area. Alternative 4's breaching of the Lower Snake dams is estimated to increase all electricity costs by $268 million a year.

Recreation — Removing dams causes a loss of recreation on the Lower Snake reservoirs and also would create new benefits on a restored natural river (to be described later under the benefits heading). The value of current recreation that would be lost under alternative 4 cannot be measured directly but has been estimated by surveying current reservoir users and estimating the value of their recreation based on expenditures and travel costs. The IEAB did not raise any major issues with regard to these estimated losses, which would be in the neighborhood of $32 million a year.

Transportation — The dam breaching alternative 4 would eliminate barging on the Snake River. Shippers, primarily grain growers, would incur increased costs to transport their products to market. To the extent that existing shipping rates of road and rail remain constant, the IEAB does not criticize the general level of these cost estimates. However, there may be costly capacity expansions of rail and highway systems that would lead to increased freight rates for rail and trucking. These increases may be exacerbated if railroads no longer face strong barging competition. The IEAB urged more analysis of these questions to reduce the present possibility of an underestimate of transportation costs.

Water Supplies — Several irrigators on the Ice Harbor pool would lose their irrigation water supplies with the breaching of the Lower Snake River dams, and, in addition, some industrial and municipal water users would be harmed. The IEAB encouraged the Corps to focus attention on the use of water by orchards and vineyards, which are responsible for most of the value of all crops irrigated from the Lower Snake river. If alternative supplies of water, such as wells, could be established for these particular crops, the costs of lost water supplies in alternative 4 might be reduced substantially.

Implementation and Avoided Costs — Implementation costs are an alternative's actual direct costs of putting the alternative into place, such as the expense of improving fish gathering for alternatives 2 and 3 and of removing the earthen portion of the dams for alternative 4. Avoided costs are future costs that would be incurred under continuation of current conditions, but that would be avoided if an alternative strategy were implemented. The usual example of avoided cost for alternative 4 is the future cost of generating equipment replacements and upgrades at the Lower Snake River dams. The IEAB urged the Corps to consider other possible future costs that would be avoided, such as those of increased Clean Water Act compliance at the dams or the requirements for fish and wildlife programs that might be unnecessary if the dams were breached.

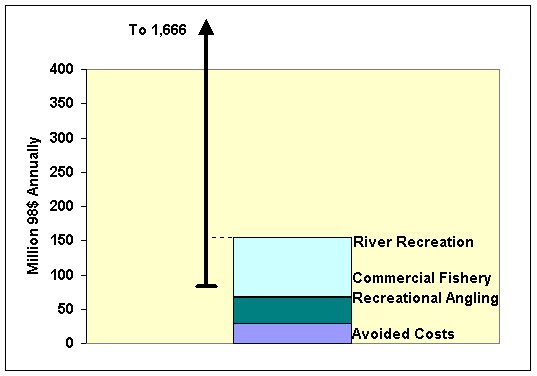

We turn now to the benefits of dam breaching. What is most significant about the estimated benefits of the dam breaching alternatives is not their most probable level, but their extreme uncertainty. In addition to the obvious benefits associated with increased tribal, commercial and recreational salmon harvest, there are values associated with non-angling recreation, with tribal wellbeing, and with the intrinsic or existence value of improvements to threatened or endangered salmon populations. Uncertainty is greatest in the estimates of the existence values. The IEAB recommended to the Corps that these values be treated separately from other benefits, and that advice is generally followed in the economic appendix. We have followed our own advice here by not including them in the display of benefits in Figure 2.

The benefits of dam breaching were estimated at $154 million per year. As shown in Figure 2, the uncertainty of the dollar benefit estimates is extremely large, ranging from $79 million to over $1600 million per year. Nearly all of this range is due to the huge range of estimates of non-angling recreation values on a restored natural Lower Snake River. The range of benefits would be even wider if the range of dollar values for existence value had been included. Each of the categories of benefits is discussed below along with IEAB comments.

Fisheries — Increased harvest levels would be associated with increased numbers of fish. This increased harvest represents an economic benefit ? of salmon recovery. The DREW estimates of various increased harvests had to be derived from making a number of assumptions about the PATH estimates of increased runs and from a possible allocation of these runs to various commercial fisheries. The IEAB review recommended more clarity in the reporting of the fishery estimates. In particular, there is a need for presentation of the numbers of fish assumed for each alternative, a clear distinction between hatchery and wild fish, and a separate identification of the tribal harvest and its increase. Further, the fishery estimates need to be updated by using the latest NMFS or PATH estimates. If this is not possible, the uncertainty of the PATH results over time should be emphasized so decision-makers can put the derived benefits in the proper perspective.

Figure 2. Benefits of Alternative 4: Breaching Lower Snake Dams

Recreation — Estimating potential values for recreational activities on a restored natural Lower Snake River is even more difficult than measuring existing recreation on the reservoirs. These estimates must be based on a contingent value survey, in which the hypothetical restored river must be described, survey respondents asked how likely they would be to visit, and the potential visits valued. The IEAB raised several issues with the results of this section. In essence, we felt that the range of values presented was unnecessarily large and that the lowest and especially the highest values were unrealistic. The survey only establishes the demand for recreation; the other part of the equation is supply. The Corps study assumed that the supply of recreational facilities on the Lower Snake would be doubled from current levels to accommodate increased demand for recreation. However, the costs of increasing these facilities were not included in the analysis. The IEAB recommended that the Corps undertake additional analysis in this area to improve the estimates and narrow the range of uncertainty.

Existence value — DREW attempted to measure the existence, or passive-use, value (benefits) of a free flowing Snake River, and of Snake River salmon without the dams. In the absence of a specific survey on people's contingent valuations, DREW made do with data from older surveys about salmon and of free-flowing streams elsewhere. There were obvious difficulties with the appropriateness of such data, and with the ingenuity needed to transfer them. In its comments the IEAB has suggested that the results may overestimate the existence value of breaching the dams. In any case, aware of the very large values obtained, we have recommended that the existence values should be prominently and clearly displayed. However, because their meaning and reliability are substantially different from those of DREW's other benefits and costs estimates, existence values should not be added in with other costs and benefits, but presented separately. These recommendations have been followed in the economic appendix.

We support the wide ranging estimates of benefits reported in the economic appendix as being the best information available now. But we also find that the information on benefits of dam breaching is not accurate enough to provide useful guidance for the momentous decisions that might be based on them. We recommended that the Corps separate the "existence value" estimates from the other information for this reason.

Our recommendation to the Council and others regarding the economic appendix is threefold: (1) consider the costs of dam breaching estimated in the economic appendix as the best estimate currently available; (2) invest in improved estimates of economic benefits from dam breaching to reduce the range of uncertainty and to improve confidence in them; and (3) in the meantime make decisions based upon the estimated costs, biological feasibility, and other measures of positive outcomes while relying less on the magnitudes of estimated recreational benefits and existence values for salmon and natural river conditions.