In 1940, the reservoir behind Grand Coulee Dam, Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake (also called Lake Roosevelt), was filling. Eventually, the rising water would cover Kettle Falls more than 100 miles upriver, erasing one of the two great Indian fishing sites on the Columbia. The other, Celilo Falls, similarly disappeared under the reservoir behind The Dalles Dam in 1957.

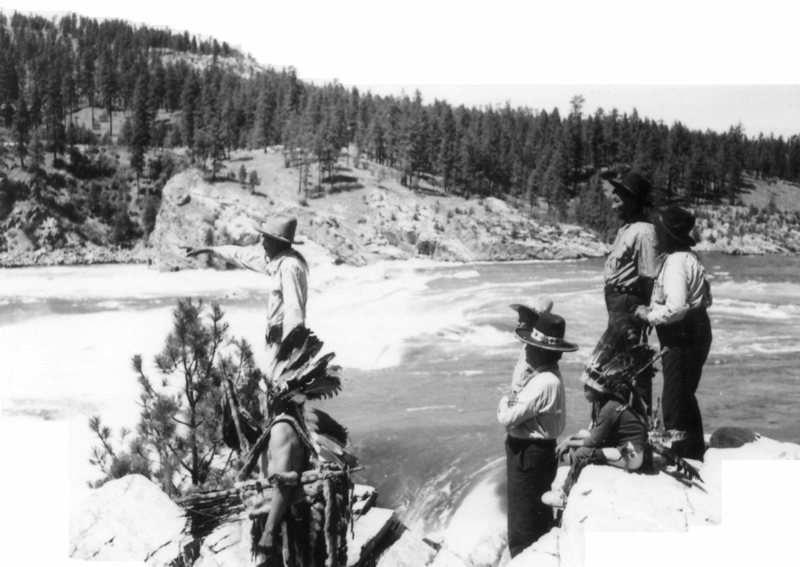

At Kettle Falls, where David Thompson watched Indians fish for salmon in 1807, the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, descendants of the fishers Thompson encountered, hosted a three-day gathering in 1940 to eulogize the impending loss of the historic falls. Appropriately, the event was called the “Ceremony of Tears.” U.S. Senator Clarence Dill, D-Washington, a longtime supporter of Grand Coulee Dam, was a featured speaker at the event on June 16, 1940.

The war in Europe was intensifying, Hitler had invaded Poland, and Dill believed the power from the big dam would be instrumental in the war effort. “We can build more airplanes and tanks and can train more pilots for national defense than any other nation or combination of nations, and the quicker we do it the better,” he said. “We know now that the only thing in this world which Hitler will respect is more force than he controls.”

Dill also acknowledged the terrible impact the dam would have on Indians by wiping out their historic fishery at Kettle Falls, but he hoped that in the loss of the fishery the Indians would realize some benefit from the power the dam would produce.

“The Indians have fished here for thousands of years,” he said. “They love this spot above all others on their reservation because it is a source of both food and of beauty. We should see to it that the electricity which the great dam at Grand Coulee produces shall be delivered to all the people without profit, so that the Indians of future generations, as well as the white men, will find the change made here a great benefit to the people.”

Considering the finality of the rising water and the life-altering impact the loss of the fishery would have on the tribes, the Ceremony of Tears was, in some respects, a pretty lively event. A reporter for the Spokesman-Review newspaper of Spokane estimated the attendance at 1,000. Chiefs of the San Poil, Colville and other bands spoke. There was a carnival, a dance at an outdoor pavilion featuring an all-Indian band and a Saturday night smoker where Indian and white boxers challenged each other.

But according to a story in the Spokesman-Review of June 18, 1940, there was a “more serious side” of the event at which the chiefs “told of their sadness of the passing of the falls, and some thought the government should reimburse them for their loss.”

According to the story, “It was a sad farewell to many Indians, who for years have visited the falls each year to catch the salmon going to the headwaters of the Columbia River to spawn. Far into the night the Indians joined in the merrymaking with the whites by attending the carnival nearby and the modern dancing. Many of the Indians were born in this vicinity and have watched the progress of the country.”

In retrospect, the Ceremony of Tears marked a historic cultural shift as well as the elimination of salmon fisheries at Kettle Falls and at other less prolific locations on the upper Columbia, in the United States and British Columbia, that had existed for thousands of years. By 1940, the dam was solidly in place and salmon could not pass. Soon the great falls would be drowned by the great dam, whose reservoir would provide water for a large-scale irrigation project on the adjacent Columbia Plateau, and whose electricity would make aluminum for about one-third of the airplanes built in the United States during World War II. Some at Kettle Falls were preparing for the future, like an Indian from British Columbia who remarked to the Spokesman-Review reporter that after the ceremony he would return home “to enlist in the British Army to fight the Germans, as he did in the last war.”

For others, the events in Europe might as well have been taking place on the moon. On June 17, the Spokesman-Review reported:

Six Indian chiefs of the Colville tribe experienced another innovation in their tribal customs when they used a loud speaker to address their people. Each chief spoke into the microphone, as did the interpreter who repeated their remarks, and all seemed to enjoy hearing their voices carried far through the pines, among which their teepees stand for the last time.

Kettle Falls slipped beneath the rising waters of Lake Roosevelt on July 5, 1941. Until 1946, salmon and steelhead continued to appear at the base of Grand Coulee Dam, trying to get upriver to spawn. After 1946, none was seen at the dam again.

Kettle Falls remains under water to this day, with the exception of occasional periods in the spring when the reservoir is drawn down to its lowest level. Then, for a few days or weeks, the tallest rocks of the falls peek above the surface. The water swirls lazily around these remnants, leaving patterns on the surface that dissipate quickly.