When the Hudson's Bay Company merged with its rival North West Company in 1821, the Bay Company acquired Fort George at Astoria, which had been built by employees of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company and acquired by the North West Company in 1813.

Following the merger the company sent George Simpson, its Governor of the Northern Department of Rupert Land, to survey the Columbia watershed. The company defined Rupert Land as all of the territory that drained into Hudson’s Bay, which was the area of the company’s royal charter. For administrative purposes, the company divided Rupert Land into northern and southern departments.

Simpson’s favorable report, despite the company’s initial lack of interest in the Columbia, led to the establishment of a trading empire that utilized many of the forts acquired in the merger, including Fort George. This was an impressive fort, but it was poorly situated for agriculture, and Simpson, by 1825 the head of the company’s Columbia Department, insisted that forts be farming enterprises as well as trading posts in order to supply food for employees and for export. As well, the location of Fort George on the south shore of the Columbia was problematic, as the company was aware that the 10-year agreement of joint occupation of the Northwest, which the United States and Great Britain negotiated in 1818, was tenuous and probably would end with America acquiring the territory south of the river. It would be best to move the fort to a better location for farming, a location closer to the interior fur trade routes and, of course, on the north side of the river.

Simpson picked location about 100 miles inland on a bluff overlooking the river within the present-day city limits of Vancouver, Washington. Fort George was abandoned, the new fort was constructed and, on March 19, 1825, Simpson christened it. Later he wrote of the occasion that he “. . .baptized it by breaking a Bottle of Rum on the Flag Staff and repeating the following words in a loud voice, ‘In behalf of the Honble. Hudsons Bay Coy. I hereby name this Establishment Fort Vancouver. God Save King George the 4th with three cheers.’” Simpson named the fort after Capt. George Vancouver “to identify our claim to the Soil and Trade with his discovery of the River and Coast on behalf of Great Britain.”

That was a fiction, of course. The American merchantman Robert Gray discovered the river on May 11, 1792. Vancouver, who had dismissed the opening of the river as “insignificant” and “not worthy” of investigation one month earlier, in April 1792, returned in October after the Spanish commander at Nootka Sound showed him a copy of Gray’s chart of the estuary. Even then Vancouver did not enter the river himself but sent a lieutenant, William Broughton, to explore it. Vancouver was a great explorer worthy of Simpson’s veneration in naming the fort, but Vancouver did not discover the Columbia River.

The original Fort Vancouver was built on a bluff above the river, but in 1828-29 was relocated about a mile to the west along the shore of the river. The location was about five miles upstream from the mouth of the Willamette River. The fort is reconstructed on that site today.

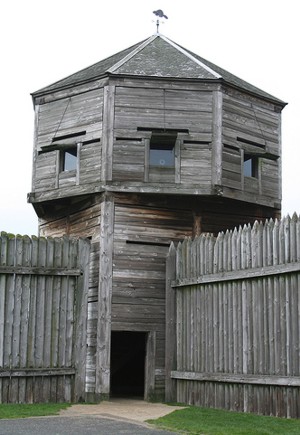

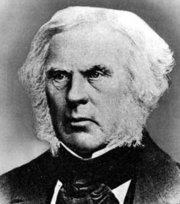

Fort Vancouver quickly became the base of the Bay Company’s Columbia Basin operations. The fort was in the shape of a parallelogram 250 yards long and 150 yards wide. It was enclosed by a wall of poles 20 feet high and supported by buttresses on the inside. There were two courts within the walls, and these were surrounded by about 40 buildings that housed offices, apartments, a bakery, a pharmacy, a retail shop and workshops for the trades people, a schoolhouse and a chapel. Only one building was built of brick and stone, the powder magazine. The two-story residence of the Chief Factor, Dr. John McLoughlin, was at the center, and it included a plaza and flower beds. There was a separate dining hall, which included a smoking room hung with weapons and Indian paraphernalia. There were two, two-story bastions, one at the northwest corner and other at the southwest corner. Each had two 12-pound cannons, but these never were used.

By the 1830s, with a population of 500 to 700, Fort Vancouver was the most important community on the Pacific Coast. The company developed a robust business in agricultural products including cattle, timber and crops and exported products to the Russian forts in Alaska, and to the Sandwich Islands and England. Fort Vancouver would be the center of the Bay Company’s operations on the Pacific for 24 years. In 1836, Narcissa Whitman, visiting the fort with her husband, Marcus, to purchase supplies before moving inland to their mission on the Walla Walla River, described the fort in her diary for September 12: “We are now in Vancouver, the New York of the Pacific Ocean. . . .What a delightful place this is; what a contrast to the rough, barren sand plains through which we so recently passed. Here we find fruit of every description, apples, peaches, grapes, pears, plums and fig trees in abundance; also cucumbers, melons, beans, peas, beets, cabbage, tomatoes and every kind of vegetables too numerous to mention. Every part is very neat and tastefully arranged, with fine walks, lined on each side with strawberry vines.”

Fort Vancouver has an important role in the history of Northwest agriculture as the site of the first large-scale farming and ranching. McLoughlin, imported about 20 head of cattle and determined not to kill any until the herd was large enough to meet all of the demands at the fort. By 1828 the herd had grown to 200, but it was not until 1836, when the permanent herd totaled 700 — McLoughlin supplied cattle to Bay Company forts at Okanagon and Colville, too — that he allowed the first cattle to be killed at Fort Vancouver. By 1838, the herd numbered more than 1,000, spread across locations from the fort to Sauvies Island and the Tualatin Plains to the southwest. The herds also included hogs, horses, and oxen. Sheep were imported from England. The fertile soil along the river also yielded abundant crops. In 1829, just four years after the relocation from Fort George, the Fort Vancouver farm produced 1,500 bushels of wheat, 200 bushels of barley and about that many of Indian corn.

With the growing herds becoming a management burden on the fort, McLoughlin established the Puget Sound Agricultural Company in 1838. The business flourished, with large herds at Bay Company forts at Vancouver, Nisqually on southern Puget Sound, and on the Cowlitz River. Dairy projects and flour — ground at Fort Vancouver — were sold to the Russian forts in Alaska; hides and wool were exported to England. As well, the company grew and sold large surpluses of wheat, oats, peas and potatoes. The Bay Company also produced lumber at two sawmills at Vancouver for export to the Sandwich Islands.

With the resolution of the international border issue in 1846, the Bay Company relocated its Columbia Department headquarters to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island.

Following a dispute with Simpson — the two never got along very well — McLoughlin retired to Oregon City and became an American citizen. This is something of an irony, for as a Bay Company employee and a British citizen, McLoughlin made sure that Americans arriving at Fort Vancouver on their way to settle in Oregon settled south of the river. The British considered the territory north of the river to be theirs. Now, in his retirement, McLoughlin adopted the country whose Columbia River interests he had opposed in his official position. This was not out of character for him, however, as he had always been kind to Americans. British Columbia historian George Woodcock notes that McLoughlin long held pro-American sentiments.

McLoughlin could be eloquent on the subject. In 1852, a year after he became a citizen, he wrote about his adopted country:

“I was born in Canada and reared to manhood in the immediate vicinity of the United States. . . . The sympathies of my heart and the dictates of my understanding, more than 30 years ago, led me to look forward to the day when both my relations to others and the circumstances surrounding me would permit me to live under and enjoy the political blessings of a flag which, wherever it floats, whether over the land or the sea, is honoured for the principles of justice lying at the foundation of the government it represents, and which shields from injury and dishonour all who claim its protection.”

The U.S. Army established a post at Fort Vancouver in 1849. The Bay Company continued trading at the fort until 1860. Today, the reconstructed fort (external link) attracts thousands of visitors annually.