2014 Columbia River sockeye return sets a record

- July 14, 2014

- John Harrison

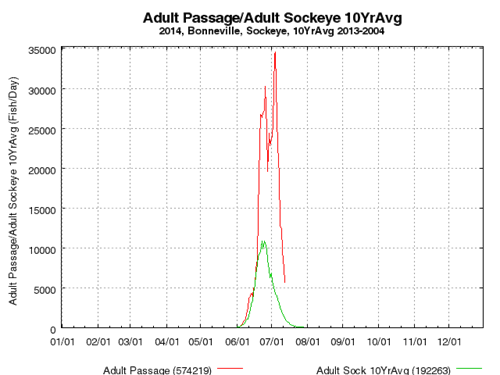

Graphic: University of Washington Data Access in Real Time website, http://www.cbr.washington.edu/dart

The 2014 sockeye run in the Columbia River is the largest since fish-counting began at the dam in 1938.

By July 13, 2014, more than 574,000 fish had passed the dam on their way to spawn in British Columbia, north-central Washington, and Idaho. The previous record was 516,000 in 2012.

Next year’s run could be even bigger, based on the number of jacks in this year’s return. Jacks are immature fish that are considered a predictor of the next season’s run size.

Sockeye return from the ocean to spawn in July and August. By far, the largest share of the Columbia sockeye run originates in Lake Osoyoos on the Okanagan River in British Columbia. The second-largest component returns to Lake Wenatchee -- expected to be about 64,000 fish this year -- and the smallest component returns to Idaho’s Redfish Lake. An endangered species, the Snake River component is expected to be about 1,200 fish counted at Lower Granite Dam this year. The number of Wenatchee and Snake River sockeye could increase, however, as the estimates were part of a forecasted total return of 347,100 fish, now greatly exceeded.

The big Okanagan run resulted from about 4 million sockeye juveniles that are estimated to have left Lake Osoyoos in 2012. Howie Wright, fisheries program manager for the Okanagan Nation Alliance, which is directing the Okanagan sockeye restoration program, said 80-85 percent of the 2014 Okanagan component are estimated to be natural-origin fish, as opposed to hatchery-origin fish. He credited the big run to improvements in water management and habitat in the Okanagan River Basin in British Columbia, favorable ocean conditions, and improvements in fish passage at Columbia River mainstem dams downriver in the United States.

He said descaling of juvenile sockeye continues to be a problem, though. Sockeye are particularly sensitive to descaling, which can weaken the fish and make them more susceptible to disease. Descaling occurs when fish bump against the walls of bypass systems at dams or pass through turbines or strike debris that accumulates in the forebay of a dam.