Dry-year Dam Operations Implemented To Protect Fish

- June 10, 2015

- John Harrison

The low runoff in the Columbia River Basin in 2015 doesn’t portend a crisis for hydropower, which is a good thing because dams in the basin provide nearly half of the electricity consumed in the Northwest. Nor is the below-average runoff from a meager snowpack creating problems for salmon and steelhead, thanks to a water-release strategy for the Columbia and Snake rivers that is implemented in dry years.

The Biological Opinion on Operations of the Federal Columbia River Power System, prepared by federal agencies to protect Endangered Species Act-listed salmon and steelhead, includes a “dry-year strategy” to boost river flows to assist migration of juvenile and adult fish, including listed species. Federal agency representatives of the Bonneville Power Administration, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Reclamation, and NOAA Fisheries briefed the Council this week in Coeur d’Alene.

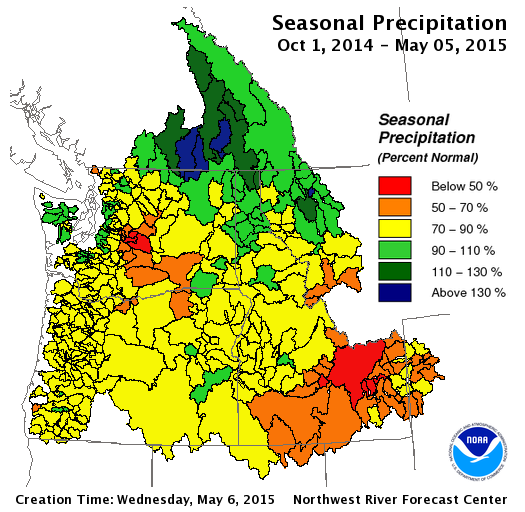

Dry year operations are implemented when the Northwest River Forecast Center, a division of the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, predicts in May that the April-through-August runoff volume at The Dalles Dam will be less than 72.2 million acre-feet, or less than 82 percent of average. The May forecast for the period was 62.4 million acre-feet, or 71 percent of average.

When dry year operations are triggered, federal storage reservoirs are drawn down farther than normal to provide more water for fish. The usual practice is to shift as much water as possible into the spring migration, with the understanding that this likely will increase the risk of having less stored water for temperature control and to refill reservoirs in the summer. More than half of the estimated 8 million acre-feet of flow augmentation for this spring and summer is being provided from reservoirs in British Columbia under the Columbia River Treaty and the Non-Treaty Storage Agreement, said Tony Norris, operations research analyst for the Bonneville Power Administration.

The additional water provided this year should result in average or near-average travel times downriver for juvenile salmon and steelhead, Ritchie Graves of NOAA Fisheries said. While flows are below objectives in the Biological Opinion,” that is expected in a dry year,” Graves said. And flows are extremely low – 51st out of the 55 lowest-flow years on record, he said.

“The bottom line for us is that we care about migration timing because fish that arrive later to the ocean generally return in lower numbers as adults than fish that arrive earlier,” Graves said. “We’re eager to see how fish respond to the hydrosystem conditions this year.”

While 2015 is a dry, low-flow year, “it’s not unprecedented,” said Steve Barton, chief of the Columbia Basin Water Management Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Barton said that while the low water is not causing any unusual navigation problems in the river, it will be “a bit challenging” to meet the many requirements for special flows and river operations through the summer.

The last time the dry year criteria was triggered was in 2010. If the current dryness continues into 2016 or later, “I’m confident we could handle it,” Barton said.