The Mystery of Swan Lake

- April 13, 2016

- John Harrison

Fish “detectives” are using biochemistry to try to unravel an intriguing mystery: How did walleye get into Swan Lake?

While “detective” is not an official job title at Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, the department is using high-tech instruments to investigate the origins of two walleye caught last October in the pristine, Northwestern Montana lake, which has 13 unique populations of bull trout, a threatened species, in its drainage basin.

Just two walleye might not sound like a threat, but the fish breed prolifically, feed voraciously and, if a population takes hold in the lake, the threat to bull trout would be very real. Sawn Lake is highly regarded for the quality of its water and habitat, particularly for bull trout. The department’s concern is shared by the fishing community. Following discovery of the fish, seven fishing and conservation organizations contributed a total of $5,000 and another contributed $10,000, adding to a reward of up to $15,000 offered by the state – total $30,000 -- for information leading to the arrest of the person or persons who introduced the predators, which are not native to the lake.

The problem is not only with walleye. Other warm-water species including crappie, perch, and lake trout also have been illegally introduced into Montana lakes.

The threat to Swan Lake is particularly troublesome, though, as the lake has been identified as a refuge for cold-water species like bull trout if the predictions of climate models prove correct and the amount of habitat for cold-water species like bull trout declines over time.

“It’s a smart place to invest in habitat and fish conservation,” Matt Boyer, fisheries mitigation coordinator for Fish, Wildlife & Parks, told the Council at its April meeting in Missoula.

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks is not after the reward, but its laboratory sleuthing could help identify where the fish came from, and that could help fishery managers as well as law enforcement address the problem. At the Missoula meeting, Boyer and Sam Bourret, Hungry Horse mitigation fish biologist for the department, described the use of microchemistry to study the ear bones, called otoliths, of the two captured walleye.

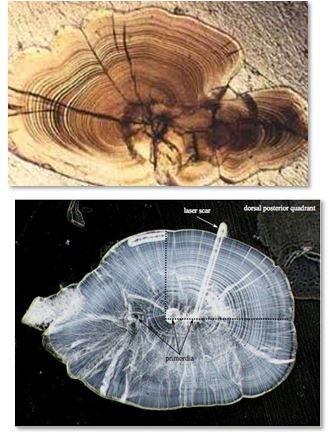

A microscopic view of otoliths with their tree-ring like growth rings

Like tree rings, concentric circles of bony growth in otoliths reveal how quickly, and for how long, a fish grew. Otoliths also contain a chemical marker that reveals the unique characteristics of the water where a fish is born and grows. The Swan Lake walleye otoliths clearly indicated the fish were born in another body of water and were in Swan Lake for only a couple of months before they were caught.

But what other water body?

Bourret compared known water chemistry profiles of several nearby lakes with the Swan Lake walleye otoliths and did not find a match. For now, then, the mystery remains. But as water chemistry profiles are compiled and made available for other Montana lakes – not all of the state’s lakes have established water chemistry profiles -- the Swan Lake mystery – and others like it – may be resolved, Bourret said.

Click here to read the Council staff memo: