What's Old May Be New Again

An experimental fish trap on the Columbia River shows promise to separate wild from hatchery fish. Illegal since 1934, might fish traps make a comeback?

- December 13, 2017

- John Harrison

What’s old may be new again in the search for a way to collect salmon from the Columbia River, keep hatchery fish for commercial sale and release wild fish back to the river unharmed. The latest innovation being tested is a technique that was used for millennia, first by native Americans and later by commercial fishers: the “pound” or stationary net, also known as a fish trap.

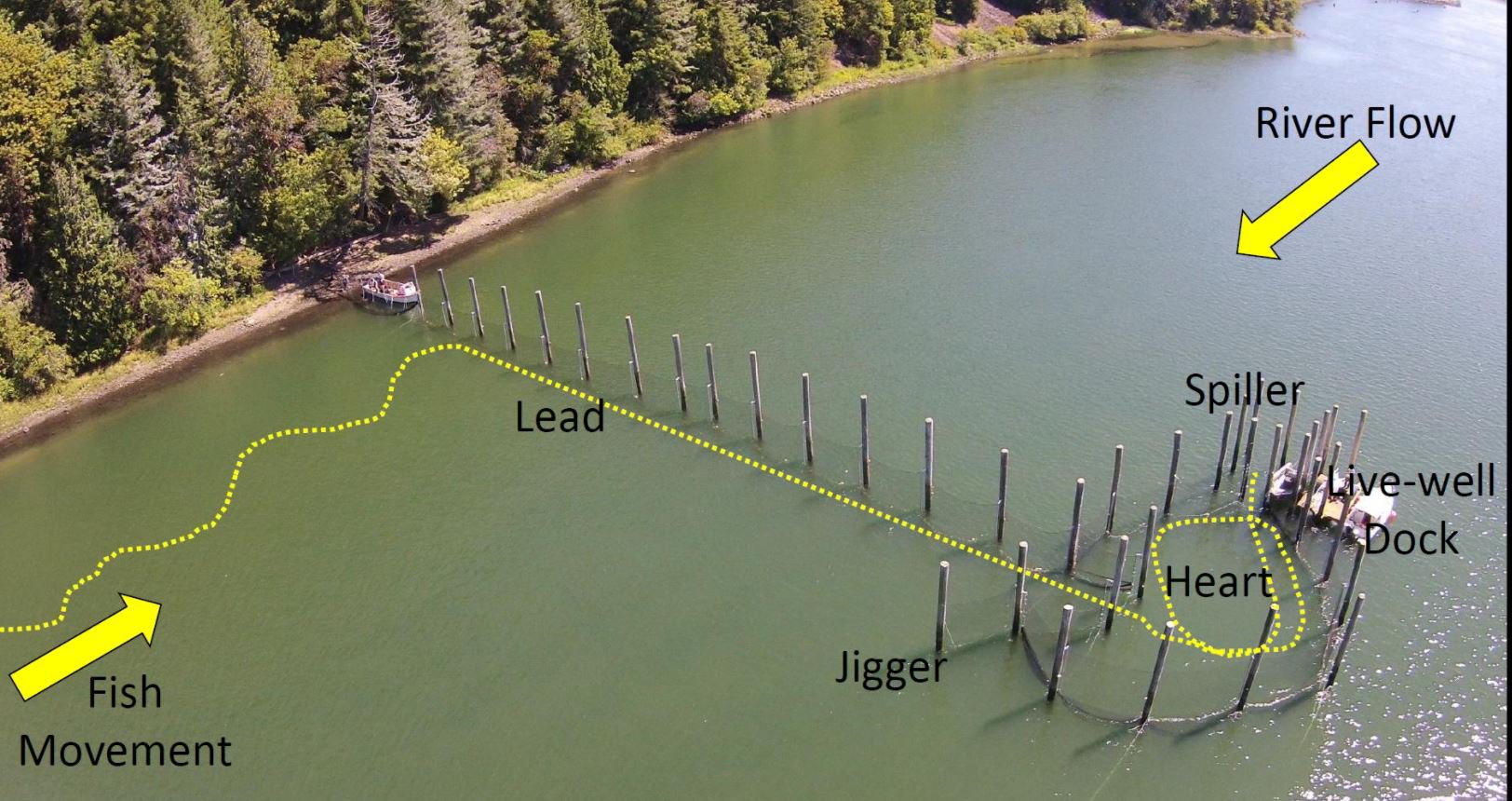

A pound net fish trap is actually a series of nets mounted on poles pounded into the river bed. The nets form a chute and trap that salmon and steelhead, which tend to always move forward, swim into but can’t escape. This allows for the fish to be observed, identified, removed for harvest, or let go. A form of what is called “fixed gear,” pound nets and other types of fixed gear, such as fish wheels, were banned in Washington and Oregon in the 1930s because they were so efficient – too efficient – at catching fish. Pound nets once accounted for about one-third of all the salmon harvested commercially in the river.

The Wild Fish Conservancy, a non-profit based in Duvall, Washington, secured funding from the Washington Coastal Restoration Initiative in 2015 to build an experimental trap in the Columbia two miles upstream from Cathlame Washington, at river mile 42, and then tested the trap in August and September of 2016. The results were promising, and a second year of experimentation took place in 2017, with funding from NOAA Fisheries, the federal agency responsible for ocean-going fish. Again the results were promising. Salmon and steelhead were caught and released back into the river mostly unharmed. This year the fish were tagged before release, and preliminary results show very high survival to a detection facility at McNary Dam 250 miles upriver.

“We concluded that traps are efficient, as you might expect, and we demonstrated they have a lot of promise to be a viable, stock-selective fishing tool,” Adrian Tuohy, fish biologist and pound net project manager for the Wild Fish Conservancy said in a presentation at the Power Council’s December meeting. “The benefits are immense, as developing alternative fishing gear is such an important topic.”

In the lower Columbia, weak wild stocks including some that are listed for protection under the Endangered Species Act, mix with more numerous hatchery-bred fish and healthy and harvestable wild fish. Accessing the target healthy fish for harvest while minimizing impacts to ESA-listed fish is a challenge for managers in both commercial and sport fisheries. Because fisheries are managed conservatively to ensure that impacts to ESA listed fish remain within conservation limits, they often fall short in catching the hatchery and healthy fish that are available for harvest.

Adding more selective tools for managers to use at particular times and locations can provide for additional opportunity for fisheries to harvest more fish while continuing to meet the conservation responsibilities. It can also be helpful in reducing the number of hatchery fish that interact with wild fish on the spawning grounds. The need for an effective way to separate hatchery from wild fish is leading many experts to reconsider the value of traps. If made legal again, their use, number, and location would have to be carefully regulated so as to not overharvest the weak runs, Tuohy said. By more effectively targeting specific fish for harvest, however, traps also could increase commercial fishing opportunities, giving an economic boost to communities along the lower river, he said.

The experimental trap on the Columbia proved successful in catching fish. In 30 days of fishing in the fall of 2016, 2,144 salmon and steelhead were caught and released. The immediate survival rate – fish released from the net -- was estimated at 99.58 percent. In 2017, the trap operated between August 26 and September 29. Bars were installed at the mouth of the trap to keep sea lions out. A total of 7,129 salmon and steelhead were caught; about 2,000 Chinook and 1,000 steelhead were tagged. The Wild Fish Conservancy’s very preliminary analysis of post-release survival of the tagged fish to McNary Dam was 99.6 percent for Chinook and 94 percent for steelhead.

“We were thrilled with these results,” Tuohy said.

Final survival rates would be scientifically analyzed in a biological assessment developed by fishery managers and established in an ESA permit prior to actual fishery use of the gear.