Small Hydro Plants Boost Snohomish PUD's Energy Supply

- October 12, 2018

- John Harrison

Two small hydropower dams in the Cascade lowlands east of Seattle take advantage of winter and spring snow and rain, producing enough power seasonally for about 3,500 homes, augmenting the power supply of the Snohomish County Public Utility District.

It’s a drop in the bucket in terms of the utility’s total load, or power demand. Snohomish, with some 800,000 residents in its service territory, is the largest customer of the Bonneville Power Administration, which markets federal hydropower in the Northwest. However, the dams, despite their seasonal and low output compared to other power plants, are important in light of the utility’s commitment to steadily increase the amount of renewable, low-carbon or no-carbon electricity in its overall power supply

“Our board of commissioners adopted a policy on climate change, and they decided they wanted their own resources,” Scott Spahr, manager of general engineering for the PUD, told the Council at its October meeting in Wenatchee. “Our climate-change initiative says we will meet all future demand through no-carbon resources like hydropower and conservation. We see these projects as long-term investments that will bring long-term benefits for the utility and our customers.”

Spahr said that rather than build the dams, which became operational earlier this year, the utility could have bought more renewable power – wind, solar -- from other providers. But the board made the decision to build new resources and build them close to the service territory if possible, rather than rely more heavily on renewable power from elsewhere in the Northwest or California. At the same time, the utility is investing in energy efficiency, or conservation, to help meet future demand for power, and those investments are reducing demand by about 9 megawatts per year.

Both new power plants, known by the names of the creeks they are located on, Calligan and Hancock, emerged as the best alternatives after the PUD considered 145 possible sites for construction. The PUD winnowed the potential sites to about 10 by rejecting those with impacts on anadromous fish (primarily salmon and steelhead), wild and scenic areas, wilderness areas, and areas protected by the Council from future hydroelectric development. Hancock and Calligan creeks drain into the Snoqualmie River above Snoqualmie Falls, which is a natural barrier to fish passage. The power plants are located approximately nine miles north of the city of North Bend.

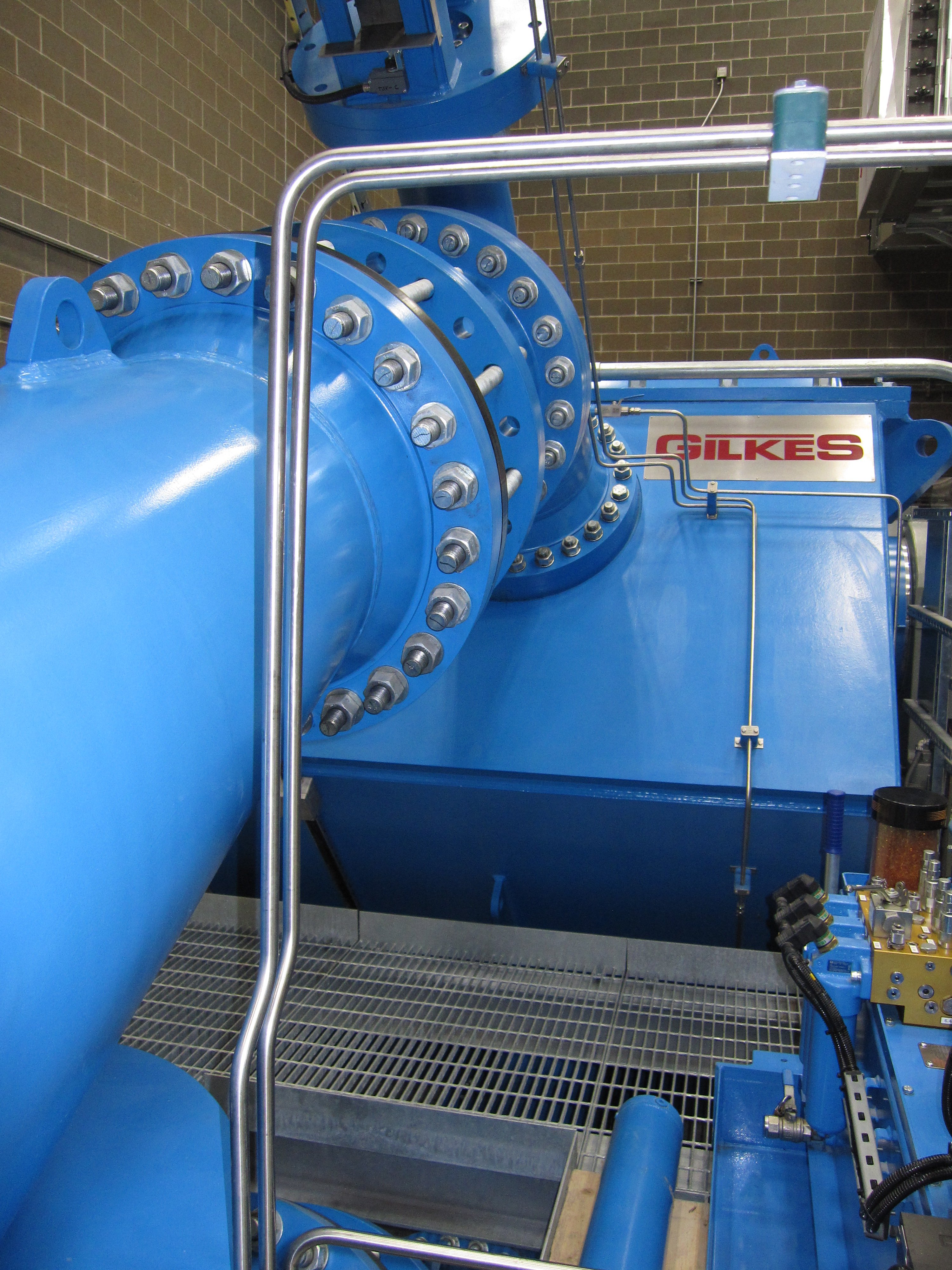

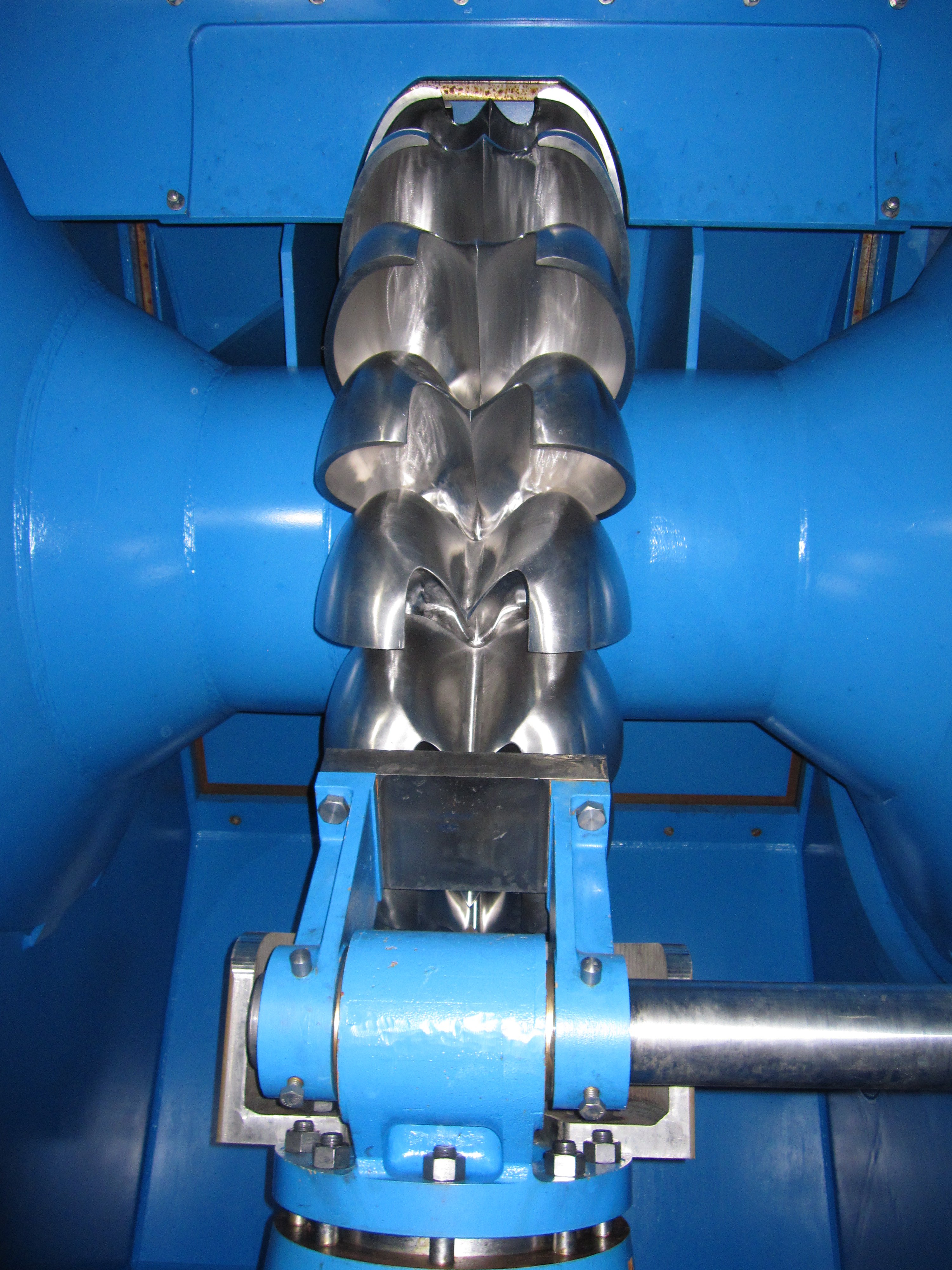

Together, at full production, the plants will produce about 4.8 average megawatts of power, which is equal to the average annual electricity use of about 3,500 Northwest homes. Both use Pelton wheel generators, which look a lot like the big water wheels that long ago powered grain mills. At the two power plants, pipelines more than a mile long carry water downhill from a reservoir or holding pond along the creek to the powerhouse. Only a portion of the water in the creek is used. Minimum instream flows are maintained in the creeks throughout the year to preserve fish habitat.

At the powerhouse, two jet nozzels spray water at a pressure of 500 pounds per square inch at stainless steel buckets bolted in a circle around a shaft. The pressurized water moves the buckets, and the spinning shaft turns a generator.

Both plants rely on seasonal rainfall, which is between 60 and 70 inches per year, typically concentrated in the fall and winter. This rainfall pattern allows for more generation during the utility’s peak energy demand period of the colder months. After being used to generate power, the water is returned to the creek. During the summer and fall, when natural stream flows are low, the plants are not operated.

The PUD worked to minimize fish and wildlife impacts by, for example, burying the penstock pipes that lead to the powerhouses, avoiding wetlands, burying high-voltage transmission lines, and building fish ladders to help resident rainbow trout pass the water intake structures.

For more information on the Calligan Creek powerplant, see https://www.snopud.com/PowerSupply/hydro/cchp.ashx?p=3316, and for Hancock Creek, see https://www.snopud.com/PowerSupply/hydro/hchp.ashx?p=3315