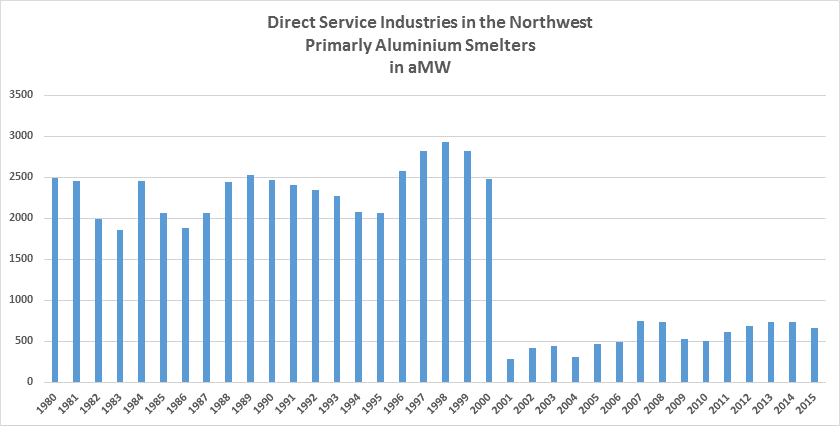

The Columbia River has a key role in the history of aluminum production in America, as the industry was the first major industrial customer of Columbia River hydropower. Over time, the industry grew to employ around 11,000 people in the Northwest and consume 3,150 average annual megawatts of electricity, enough to light three cities the size of present-day Seattle for a year. But rising costs of electricity and labor, and intense competition in the world aluminum market made it increasingly difficult for the 10 Northwest smelters to compete, and by the end of the 20th century most of the region’s smelters were closed and/or facing an uncertain future (Richard Hanners, a former aluminum plant electrician and editor of newspapers in Whitefish and Columbia Falls, Montana, currently (2018) a reporter at the Blue Mountain Eagle in John Day, Oregon, wrote a comprehensive history of the Columbia Falls, Montana, aluminum smelter).

The electrolysis technique of producing aluminum from bauxite requires large amounts of electricity delivered steadily. With Bonneville Dam coming online in 1938 and the region hungry for economic expansion, the aluminum industry seemed promising for the Pacific Northwest. That year J.D. Ross, first administrator of the Bonneville Power Project (it was renamed the Bonneville Power Administration in 1940), commented in the Project’s first annual report that industrial development and national defense would be important uses of electricity from the dam. But he did not mention aluminum. Ross didn’t favor aluminum because smelters used large amounts of power but did not employ large numbers of people. He thought the aluminum industry should stay out of the Northwest in favor of other, more labor-intensive industries until the completion of Grand Coulee Dam in 1941.

However, the Bonneville Project faced tough questioning in Congress in 1938 and early 1939 about its low revenues. The Project needed to boost its sales to satisfy Congress, and aluminum was the answer. Ross died in March 1939, and in May President Roosevelt appointed Frank Banks of the Bureau of Reclamation as a temporary replacement. A conservative Republican, his ties to private business made him unpopular with public power advocates and New Deal Democrats. Banks would go on to be a key figure in the construction of Grand Coulee Dam, but his tenure as Bonneville administrator ended in September when Roosevelt appointed Paul Raver as permanent administrator. Raver signed a contract with ALCOA in December to supply electricity — initially 32.5 average annual megawatts — for a smelter at Vancouver. The first transmission line from the dam was completed to Vancouver at about the same time. With that smelter the Northwest aluminum industry was born.

Other aluminum smelters soon were constructed. Reynolds Metals Company constructed the next one, at Longview, Washington, about 40 miles north of Vancouver, in 1941. Other plants were built by the Defense Plant Corporation, which was formed by the federal government to invest in industrial production. The plants were dispersed geographically around the Northwest so that they could benefit multiple communities and be sold after the war. Each bought electricity primarily from Bonneville.

Boeing, which was building warplanes in Seattle, was a primary customer for aluminum from Northwest smelters. It has been estimated that electricity from Grand Coulee Dam alone provided the power to make the aluminum in about one-third of the planes built during World War II.

Following the war, aluminum production crashed and hundreds of workers were laid off. But production rebounded, and by 1946 the region produced 36 percent of the nation’s supply of ingots; by the 1950s it was 40 percent. The Defense Plant Corporation’s plants were sold to Reynolds and Kaiser after the war at low prices in order to encourage competition in the industry dominated by ALCOA.

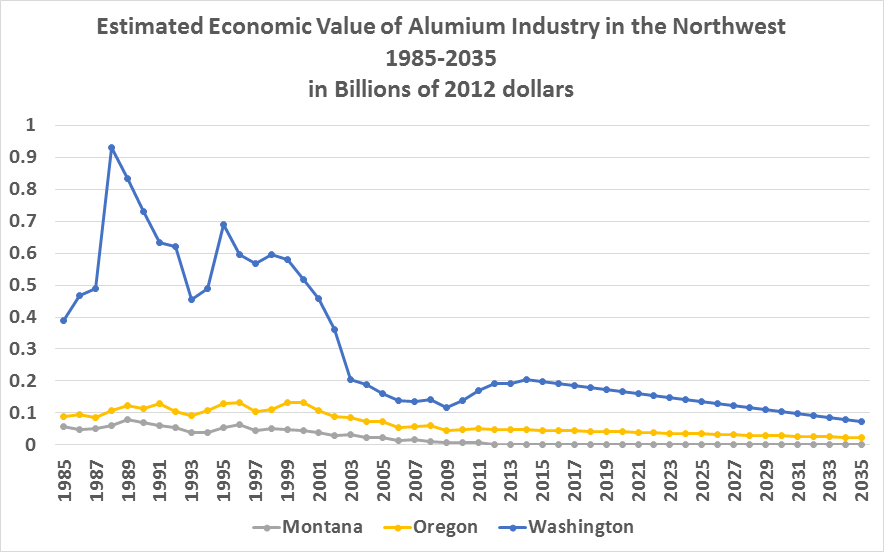

Through the 1950s and 1960s the industry prospered and the number of aluminum smelters grew to 10. At full operation, the plants employed around 11,000 people, a small percentage of the region’s workers. But the jobs paid well, and the plants had benefits for Bonneville and the Northwest. They consumed large amounts of hydroelectricity at steady rates of demand, thus providing significant income to Bonneville and operational consistency for the dams. They provided economic benefits to the communities where they were located, communities as diverse as rural Goldendale, Washington, and Columbia Falls, Montana, and as urban as Spokane and Tacoma.

The smelters accounted for 40 percent of the smelting capacity in the United States and 6 to 7 percent of the world’s capacity. The aluminum companies paid millions of dollars to Bonneville, and this important income helped Bonneville provide many power-related benefits to its customers and environmental benefits to the region, particularly after Congress approved the Northwest Power Act in 1980.

The Power Act was something of a watershed for the politically powerful aluminum companies. In the Power Act, the aluminum companies, and the several other direct-service customers of Bonneville, got what they long had wanted — long-term power sales contracts. In exchange, the companies agreed to pay a premium in those contracts to finance the “residential exchange,” an important element of the Power Act in which Bonneville exchanges its low-cost power for like amounts of higher-cost power produced by investor-owed utilities so that all residential and small-farm electricity customers in the Northwest would pay approximately the same per-kilowatt-hour charge. The direct-service customers paid the difference.

For the aluminum companies, the Power Act meant rate increases but also stable long-term costs for power. It made sense at the time, given the chaos caused by the rising costs and increasing public disillusionment over the participation by Bonneville and many of its customers in building five nuclear power plants to augment the hydropower supply. See the discussion of nuclear power under the heading “hydro-thermal power program.” Bonneville already was raising its rates in response, and they would go up more — a lot more. Between 1979 and 1983, Bonneville raised its rates nearly 250 percent.

The aluminum companies were not immune, despite the contract provisions of the Power Act. It was a devastating blow. Before the increases the companies enjoyed very competitive rates from Bonneville, compared to the prices paid for power by their competitors. Now, their position in the global marketplace was eroding as a result of increasing costs for power. Bonneville funded an energy conservation program for the smelters, but efficiencies were expensive and difficult to achieve at the aging smelters.

Problems continued to mount for the aluminum companies as they struggled to stay competitive in the world marketplace in the 1990s. In 1996 the relatively brief history of aluminum smelting in the Northwest began to unravel. To keep the industries as customers, Bonneville tied its smelter rates to the worldwide price of aluminum, but still the companies struggled. In 1996 and 1997 the smelters gave up some of their long-term contracts with Bonneville in exchange for increased access to the wholesale power market, where electricity was less expensive than Bonneville’s. As a result, Bonneville reduced the power it supplied to the smelters to about 60 percent of their previous contracted amount, and reduced it further in 2001 to 40 percent or about 1,425 megawatts. Meanwhile, technological advancements and the construction of new smelters in other countries with lower labor and power costs further disadvantaged the Northwest smelters.

The West Coast energy crisis of 2000 and 2001, when a power shortage drove wholesale prices up by factors of 10 and 20 or greater, may have been the final blow. By the summer of 2001, all 10 aluminum smelters were shut down or were operating at very limited and periodic production. Practically everyone on the West Coast experienced a rate increase during the energy crisis or as a result of it, including Bonneville and the aluminum companies. Two companies, ALCOA and Golden Northwest Aluminum, proposed to build their own natural gas-fired power plants and share the output with Bonneville, but discussions broke down over issues of construction costs and power pricing. Ultimately, the aluminum companies simply no longer could compete.

There is little optimism that Northwest smelters ever will resume full production. Low-cost electricity lured the aluminum companies to the Northwest in the 1940s and 1950s; increased prices for raw materials, volatile electricity prices, and worldwide competition with other, often lower-cost production and supply, eventually drove them out of business.

In 2016, ALCOA idled its smelters in Wenatchee and Ferndale, the last two operating in the Northwest. The company retained its power purchase contract with the Chelan County Public Utility District in case the Wenatchee smelter might restart in the future. If the plant were not restarted by June 2017, ALCOA would owe the PUD $67 million. In May 2017, the PUD agreed to ALCOA's request to change the contract to "preserve the opportunity to further consider restarting its aluminum smelter," according to a PUD news release. Alcoa agreed to pay $7.3 million, which includes a charge for being able to “buy time,” according to the PUD. Citing a shrinking worldwide surplus of aluminum and a Trump administration proposal to investigate unfair trade practices in the global aluminum market, an ALCOA official told the PUD commissioners at a recent meeting that the company is more optimistic that it might be able to reopen the Wenatchee smelter. ALCOA has not announced when that might happen.

Both charts: Massoud Jourabchi, Northwest Power and Conservation Council