In January 1943 the Defense Plants Corporation, which at the time was establishing new electrometal and electrochemical plants in the Pacific Northwest to use the hydroelectricity of Grand Coulee and Bonneville dams, asked the Bonneville Power Administration to supply electricity for a new “mystery load” at Hanford, a tiny farming community on a bend in the Columbia River in the dusty, dry, and wind-swept Columbia Plateau of central Washington. World War II was in its second year, and the Atomic Energy Commission had acquired 670 square miles of land in the Hanford area for a project related to the war effort, but that was all that was known.

The Manhattan District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, created the previous year, built the Hanford Engineer Works, employing thousands of people in a secret project to separate plutonium from uranium to make nuclear bombs. Enrico Fermi had achieved nuclear fission at the University of Chicago for the first time in 1942. Now the U.S. Army was racing to develop the bomb before Hitler’s scientists did. The Manhattan Project, authorized by President Roosevelt in December 1942, included laboratories on the Clinch River in Tennessee, at Los Alamos, New Mexico, and at Hanford.

Building the Hanford Engineer Works required the forced relocation of two communities, Hanford and White Bluffs, and more than 1,500 people, including farmers, ranchers and the local Wanapum Indians, whose fishing sites and camps dotted the Hanford reservation and Columbia River shoreline. The Indians relocated west of the Hanford site at Priest Rapids. Developed areas, including homes and ranches, were condemned by the Army; after the owners left, many of the abandoned homes were used by the Army as temporary living quarters and offices. Many people objected to the government’s appraisals of their property and argued for higher payments; in most cases, the Army negotiated and settled out of court. When the Manhattan Project buildings were complete, the homes and community buildings were torn down. Only the concrete remains of building foundations mark the former town sites today.

Construction began at Hanford on March 22, 1943. E.I Du Pont de Nemours and Co. was the site contractor. The work included simultaneous construction of three reactor complexes, two chemical separations complexes, a center for fuel manufacturing and research, a construction camp and an employee village. In 30 months, a total of 554 buildings were constructed, not including residences or dormitories.

The Army selected Hanford as the site of its secret bomb laboratory for several key reasons. First, it was isolated, and the Army demanded secrecy. The secret almost leaked in April 1944 when Oregon congressman Homer Angell defended appropriations for the project by publicly referring to the “mystery load” of electricity that was needed at Hanford for “a new weapon of warfare, developed by new manufacturing processes that will turn large volumes of electricity into the most important projectile yet developed.” The wartime Office of Censorship tried — unsuccessfully — to stop the Oregon Journal newspaper of Portland from publishing a story about Angell’s remarks. The secret, however, remained intact. Second, there was an abundant supply of clear, cold water in from the Columbia River, and the reactors required cold water to dissipate the heat generated by nuclear fission. Third, the reactors and the chemical plants required large amounts of electricity, and the governments two new hydropower dams at Grand Coulee and Bonneville were close — Grand Coulee, was just 90 miles north.

The Manhattan Project reactors at Hanford were squat and non-descript. Each measured 36 feet long and 28 feet tall. Each used 200 tons of uranium-metal fuel and 1,200 tons of graphite to control the nuclear fission in the uranium piles. Six reactors were planned, spaced at one-mile intervals along the southern shore of the river as it bends through the Hanford site. Each reactor site was assigned an alphabetic identification, A through F. The B, D and F reactors were build first at alternating locations that averaged six miles apart. Each site was self-contained. This ensured isolation from other sites, workers and the nearby population in case radioactivity leaked or there were an explosion. The chemical separation plants, which did not require Columbia River water, were built 10 miles south of the reactors, separated from them by Gable Mountain and Gable Butte.

The first reactor, at site B, began operating on Sept. 26, 1944. The first plutonium was delivered to the Army on February 2, 1945. The first test blast was on July 16, in New Mexico, and nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki three days later. The plutonium in the second bomb was manufactured at Hanford. The war ended soon after.

Columbia River hydropower helped build one of the two bombs that ended World War II, but the war didn’t turn on the availability of massive amounts of hydropower despite the assertions of some people, including President Harry Truman. Campaigning in Pocatello, Idaho, in 1948, Truman commented: “Without Grand Coulee and Bonneville dams it would have been almost impossible to win this war.” Earl Warren, the Republican vice presidential candidate the same year, said Hitler would have developed the bomb first if not for Columbia River hydropower. The truth, however, is that Columbia River hydropower made the Hanford site possible, but Hanford was just one of six sites where the Army considered building the secret engineering and production facility. There were no nationwide power shortages during the war, and if another site had been selected the government would have diverted electricity from domestic uses if necessary. In fact, historians have asserted that the Columbia River dams didn’t win the war as much as the war won the public relations battle over the dams. The war effort brought an influx of people and industry to the region and boosted the regional economy. The war helped legitimize the government’s gamble in building the big dams.

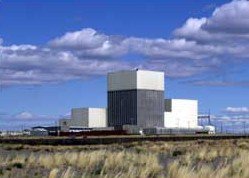

Today the Hanford site encompasses 586 square miles. Over time, the plutonium production complex grew to nine reactors, all now closed. Hanford is the site of the only operating nuclear power plant in the Northwest, the Columbia Generating Station operated by Energy Northwest. Construction began in the 1970s on that plant and on two other nuclear plants at Hanford, all planned as part of the Hydro-Thermal Power Program. The two others never were completed. Battelle Pacific Northwest Laboratories also has research facilities at Hanford, but the primary focus of work is the federal Department of Energy’s effort to clean up the radioactive waste left over from the Manhattan Project.

The magnitude of the radioactive contamination at Hanford is staggering. Much of the waste is liquid — about 53 million gallons — as the chemical extraction process used at Hanford involved soaking the spent uranium fuel rods from the reactors in nitric acid to separate the plutonium. Liquid wastes are stored in 177 underground tanks; 70 are leaking, and a plume of radioactivity is seeping toward the Columbia. There are 1,700 waste sites and about 500 contaminated buildings.

The cleanup plan, which is being implemented by the federal Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the state of Washington Department of Ecology, calls for pumping liquid wastes from tanks (single-shell tanks first) and combining the liquid with molten glass, a process known as vitrification, for eventual burial in a waste depository. The Hanford waste also includes 75,000 barrels of solid radioactive waste, most of which remains buried in trenches but is being removed. Solid waste also includes spent fuel rods, such as the 2,300 tons of spent fuel stored underwater in large, concrete pools at the two K Basin reactors. The pools had stored cooling water for the reactors when they were operating. Spent fuel rods exposed to air can burn, possibly spreading radioactive ash and particles.

The spent fuel in the two K Basin ponds, was deteriorating and so beginning in 1994 crews removed it and, over time, moved it to Hanford’s Canister Storage Building, where it will remain until a permanent, national repository for spent fuel is built. Once the spent fuel was removed, some 47 cubic yards of radioactive sludge was removed from the bottom of the two ponds and stored in containers.

Radioactivity contaminated the Columbia River during the 1940s and 1950s when the defense reactors were operating. The earliest Hanford reactors were designed to use river water for cooling and return the water directly to the river. Later reactors held cooling water in ponds to reduce its radioactivity before being released to the river. Since then, radioactivity that leaked from the ponds contaminated groundwater. In 2017 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported that tests showed groundwater was contaminated with hexavalent chromium and strontium-90. In some areas, plumes of contaminated groundwater reached the river. Crews have employed several strategies to block the plumes, all of which are intended to decontaminate the soil and ground water.

The U.S. Department of Energy maintains a Hanford website with up-to-date information on the cleanup.