Dr. John McLoughlin, an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company, was the Chief Factor, or trader, at Fort Vancouver from 1825, when the fort was constructed as headquarters of the company’s Columbia River Department, to 1846. In this position he was the most important European in the Northwest. Historians Dorothy Johansen and Charles Gates write that McLoughlin was “the chief figure of Northwest history” during his tenure at Fort Vancouver.

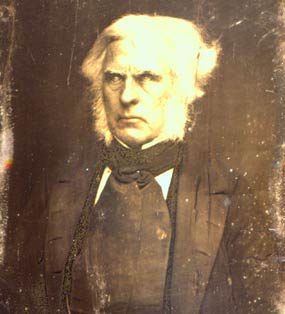

McLoughlin was about six feet tall and heavy, with a dignified if bland manner. His hair was prematurely gray — hence, the nickname was given by local Indians, “the silver-haired eagle” — and he had a temper. His subordinates called him “the Emperor.” George Simpson, Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Canada and McLoughlin’s superior, wrote of him: “A very bustling active man who can go through a great deal of business but is wanting in system and regularity and has not the talent of managing the few associates and clerks under his authority; has a good deal of influence with the Indians.... Altogether a disagreeable man to do business with as it is impossible to go with him in all things and a difference of opinion almost amounts to a declaration of hostilities, yet a good hearted man and a pleasant companion.”

McLoughlin’s accomplishments at Fort Vancouver have been well-chronicled. Less apparent in retrospect, perhaps, is the love he had for the Northwest generally and America particularly. Following the Treaty of Oregon in 1846, when the United States and Great Britain agreed on the 49th parallel as the dividing line between the two countries, the Hudson’s Bay Company steadily consolidated its business and holdings north of the border.

McLoughlin left the company in 1846 largely for personal reasons. Simpson, with whom McLoughlin always had a difficult relationship, had promoted two men of shorter tenure to positions of equal authority with McLoughlin and, at the same time, reduced McLoughlin’s salary.

McLoughlin retired to Oregon City and became an American citizen. This is something of an irony, for as a Bay Company employee and a British citizen, McLoughlin made sure that Americans arriving at Fort Vancouver on their way to settle in Oregon settled south of the river. The British considered the territory north of the river to be theirs. Now, in his retirement, McLoughlin adopted the country whose Columbia River interests he had opposed in his official position. This was not out of character for him, however, as he had always been kind to Americans. British Columbia historian George Woodcock notes that McLoughlin long held pro-American sentiments.

McLoughlin could be eloquent on the subject. In 1852, a year after he became a citizen, he wrote about his adopted country:

I was born in Canada and reared to manhood in the immediate vicinity of the United States. . . . The sympathies of my heart and the dictates of my understanding, more than 30 years ago, led me to look forward to the day when both my relations to others and the circumstances surrounding me would permit me to live under and enjoy the political blessings of a flag which, wherever it floats, whether over the land or the sea, is honoured for the principles of justice lying at the foundation of the government it represents, and which shields from injury and dishonour all who claim its protection. [Woodcock, Pages 76-77]

It is ironic, then, that in his final years he fought the Oregon territorial government over the validity of his land claim at Oregon City. His opponents were men who long had despised the Hudson’s Bay Company and continued associate it with McLoughlin, who acquired the land while still a company employee. Religious prejudices also played a part, as McLoughlin was Catholic and his dispute over the land claim grew from a confrontation with the Methodist missionary Alvin F. Waller, who had a mission at Willamette Falls. The matter ended up in Congress, where anti-British sentiment worked against McLoughlin and where, also, a memorial signed by his supporters at Oregon City was read on his behalf.

McLoughlin died in September 1857; in 1862, the Oregon Legislature officially conveyed his Oregon City land claim, except Abernathy Island in the Willamette River, to his heirs for $1,000.