Salmon and steelhead, species of anadromous fish, once were prolific in the Columbia River. Based on late 19th-century cannery records and Indian accounts, it is believed that some 10 million to 16 million adult salmon and steelhead returned to the river each year to spawn prior to about 1850, when European emigration into the basin began to accelerate, and with it the exploitation of salmon. In modern times, by comparison, the returns rarely top 2 million per year.

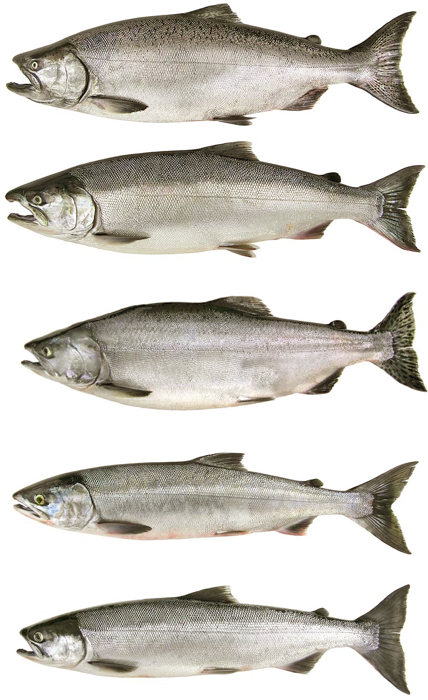

Six species of Pacific salmon are known to have inhabited the Columbia River Basin historically. These are Chinook, coho, sockeye, chum and pink salmon, and steelhead. Steelhead were grouped with trouts in the Salmo genus until the 1990s, when they were reclassified in the Oncorhynchus genus with salmon.

Oncorhynchus means “hooked snout,” a physical characteristic of adult salmon when they are ready to spawn. Five of the six species still are found in the Columbia River. Columbia River pink salmon are extinct, but pinks are prolific in rivers farther north, in British Columbia and Alaska.

The ancestors of modern Columbia River salmon probably evolved around 25-35 million years ago during the late Oligocene period. However, the fossil record of anadromous fish in the Columbia and Snake rivers dates to 7-10 million years ago, a period when both rivers ran to the sea (the Snake entered the ocean in present-day northern California). Scientists disagree whether salmon — in the Columbia River and elsewhere — evolved in freshwater or saltwater. The archaeological evidence leans toward freshwater because the fossil record suggests the freshwater residence of salmon predates their saltwater residence.

At some time in the distant past, most likely during the late Oligocene Epoch about 30 million years ago, the oceans began to cool. Cooler water is more productive of food organisms for fish than warmer water, and it is believed that salmon adapted anadromy to take advantage of this increased marine food productivity. By 8 million years ago, the Pacific Ocean achieved its current temperature regime; by then, salmon similar to those we know today had been living in coastal rivers for about 2 million years.

But some ancient salmon looked nothing like the fish we know today. One ancient species in the Oncorhynchus genus was six feet long and had a pair of enormous curved teeth that stuck out from the sides of the mouth like spikes, appearing as the fish transitioned from salt water to freshwater to spawn. This was not unlike today's salmon, which grow pronounced teeth as they prepare to spawn, but the ancient fish, and its prominent teeth, were bigger, and the teeth were more sideways than vertical. This fish, smilodonichthys rastrosus, the six-foot-long spike-toothed salmon -- some scientists called it a saber-tooth salmon, like the tiger -- may have looked ferocious, but it fed primarily on plankton and appears to have used streams for spawning. Fossil remains of the fish have been found in central Oregon and in coastal rivers in California. The species first appeared about 12 million years ago and disappeared a about 5 million years ago.

Over time the various species of Pacific salmon adopted unique life histories and run timing, adapting to localized conditions of climate and habitat. Within the same river basin, the various species adapted to particular niches of habitat. In the Columbia River Basin, chum salmon spawn in the lower reaches of the mainstem river, rarely found above Bonneville Dam 140 miles inland from the ocean. Juvenile chum salmon migrate to the sea shortly after hatching.

Chinook salmon spawn in the mainstem Columbia and its larger tributaries. There is a distinct lower-river run, generally found downstream of The Dalles and Bonneville dams, and a distinct upriver run. The lower-river fall Chinook are known as tules (TOO-lees), and when they return from the ocean they are ready to spawn. Their sides have lost their silvery luster and turned quite dark; their hooked snouts and breeding teeth are well-developed. The upriver fall Chinooks retain their bright sides and firm flesh as they swim through the lower river. Their sides remain bright until they reach their spawning grounds. “Upriver bright” is a term for these upriver fall Chinook, which are favored by commercial and sport fishers for their large size and firm flesh.

Chinook are divided among spring, summer and fall subspecies, depending on what time of the year they return from the ocean to spawn. In the Columbia, spring Chinook begin their journey to the spawning grounds from March through May, summer Chinook return from June through July, and fall Chinook return from August through November. There are no winter-run Chinooks in the Columbia, unlike rivers farther south, such as the Sacramento. Spring Chinook and steelhead spawn in headwaters areas of tributaries. The juvenile spring Chinook spend a year in freshwater before going to the ocean. These fish also are called “stream-type” salmon because they spend their first year or so in the streams of their birth.

Summer Chinook spawn in the middle reaches of tributaries. In the Snake River Basin, summer Chinook are known as spring/summer Chinook because they have adapted a life history similar to the spring Chinook that spawn higher in the tributaries. Like spring Chinook, the spring/summer Chinook spend a year or so in the habitat after hatching before going to the ocean. In the Columbia tributaries, however, summer Chinook tend to spawn in the lowest reaches of tributaries.

Fall Chinook, such as those in the Hanford Reach and the Snake River, spawn in the mainstem river and the lower reaches of its tributaries. Fall Chinook juveniles can migrate to the sea a few months after hatching. Because they leave for the ocean sooner than other salmon species, fall Chinook and most summer Chinook salmon are known as “ocean-type” salmon.

Steelhead in the Columbia River Basin, which have a similar life history to spring Chinook, return from the ocean between June 1 and November 1, with that time period about evenly split between summer steelhead and winter steelhead, although winter steelhead also can return after November 1. Summer steelhead spawn in tributaries throughout the anadromous fish range of the Columbia River Basin; winter steelhead are found mainly in tributaries downstream of Oregon’s Deschutes River. Columbia River coho, which also have a stream-type life history, return from the ocean between late August and early November. Sockeye, unique among salmon species because they spawn and rear in lakes, can spend up to two years in freshwater before going to the ocean. They return about June 1 through August 1.

Historical abundance

Lewis and Clark commented on the abundance of salmon in the Columbia. The expedition arrived at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers in October 1805, probably just after the peak of the fall Chinook run. They saw Indians fishing for salmon and, along the shores, Indians drying salmon on racks and pounding it into solid blocks of meat to be stored for future use. Salmon and steelhead were a primary food source for Columbia River Indians, more so in the lower reaches of the river where the fish were more abundant than in the farther upriver parts of the basin.

Rev. Gustavus Hines, whose Wild Life In Oregon, published in 1881, described the pioneer life and included descriptions of industries and natural resources, called the Columbia the “Mississippi of the Pacific Slope.” Hines arrived in Oregon in 1840 to assist the Rev. Daniel Lee at his mission at The Dalles. At The Dalles he joined a community of missionaries that included 25 adults, their 18 or 19 children and numerous children of the local Indians. The missionaries farmed several hundred acres and kept herds of horses and livestock. Hines familiarized himself with his surroundings; the subtitle of his book promised adventure: “Being a Stirring Recital of Actual Scenes of Daring and Peril Among the Gigantic Forests and Terrific Rapids of the Columbia River.” About salmon, Hines wrote:

Doubtless there are rivers in the world which afford a greater variety of fish, than this [Columbia], but perhaps there are none that supply greater quantities. Sturgeon are caught in abundance, but salmon is the principal fish. Of these, there are various kinds, but in this country they are generally distinguished by the names spring-salmon and fall-salmon. They literally fill the rivers of Oregon, in their season. And at all the falls and cascades in the various rivers of the country, the quantities taken and that might be taken, are beyond calculation. As they penetrate far into the interior, they afford almost inexhaustible supplies to the Indian tribes of the country, as well as the whites, many of whom depend almost entirely upon such supplies, for the first year, after settling in the country.

Salmon were a staple food source for early pioneers in the lower Columbia River Basin, including the Willamette River valley. In 1833, for example, the region’s first school teacher, John Ball, a lawyer and businessman who taught at Fort Vancouver during the winter of 1832-33, wrote: “Deer and elk are plentiful, and one can always get salmon at the [Willamette] falls to eat. Hogs, horses, and cattle are easily raised.”

Over time commercial fishing for salmon grew to be an important industry on the Columbia, particularly in the lower river downstream of the Portland/Vancouver area, as did sport fishing for salmon and steelhead in the Columbia and its tributaries. Salmon runs declined over time for a variety of reasons, from overfishing to the impacts of dams and the destruction of spawning and rearing habitat.