The Columbia River has a long history of shipwrecks. Its bar, where freshwater and saltwater meet, is one of the most difficult crossings of any river in the world, especially in the spring when the river’s volume is so great that the freshwater plume extends 100 miles to sea, and in the winter when storms lash the jumble of waves to 50 feet and higher.

Historically, the crossing was particularly difficult for ships under sail because the two natural channels across the bar forced them to turn sideways to the current and the wind. To this day it is not uncommon for ships to wait a week or longer for the bar to calm enough to allow a safe crossing.

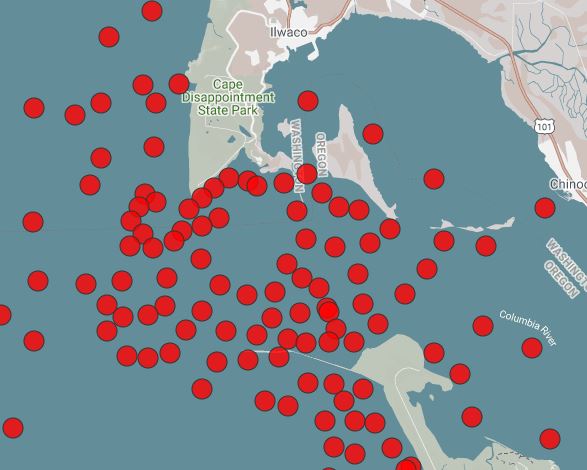

The mouth of the Columbia and the near-shore areas to the north and south are littered with shipwrecks. More than 200 are known to have occurred. Some, like the Peter Iredale, which ran aground on the Oregon shore south of the river in 1906, are visible to this day.

Shipwrecks in and around the mouth of the Columbia date to the early 1800s, but there is circumstantial evidence of shipwrecks on the coast long before that. Spanish ships may have wrecked in the early 1700s, probably driven ashore in storms. There is circumstantial evidence, too, that crews were captured by Chinook and Clatsop Indians and then traded to other tribes as slaves.

Between 1769 and 1776, Spain established presidios and missions along the Pacific coast of New Spain — present-day Mexico and southern California — in a resurgence of interest in Northwest exploration and conquest. Spanish galleons, huge ships that were up to 2,000 tons and 150 feet long, made annual trips between Manila and Acapulco, a distance of about 7,680 nautical miles, sailing a circular route that brought them eastward in northerly latitudes and then west in more southern latitudes.

Crossing eastward, it was their practice to sail north to catch the Japan current. Then, about 200 miles off the coast of present-day central California, they would turn south toward the outposts of New Spain. It was a perilous voyage. Pirates preyed on these ships around The Philippines, and near the Pacific coast fierce storms sometimes blew the ships far off course to the north and sank them or wrecked them on the coast.

The most persistent story about shipwrecked 18th-century sailors on the Northwest coast, told in variations, involves the survivors of a ship or ships that grounded on the present-day Oregon coast and later were attacked by local Indians. The survivors might have been Spaniards or, in one version of the story, Japanese swept across the ocean by eastward currents. The incident might have happened around 1700 or 1750; in fact, there probably were multiple shipwrecks along the coast in this era. Some of these survivors were said to have buried treasure chests ashore. If so, the treasure hasn’t been found — or reported to have been found, at least.

There are Chinook and Chehalis Indian legends about white men who emerged from “a whale with two spruce trees standing upright on it” which had washed up on the shore near present-day Seaside, Oregon, in the mid-1700s. Three or four bearded, pale men emerged, making signs that they wanted water and gave the Indians copper kettles and pointed inland, gesturing that they wanted the kettles filled with water. Instead, the Indians took them prisoner and scoured the ship for copper and brass. Of the survivors, at least one died and two were kept as slaves. Another version holds that the survivors escaped and worked their way upriver on the Columbia to the Cascades or The Dalles, where they settled, married native women and had children. In 1811, an aged blind man living at The Cascades, who said his name was Soto, claimed his father was a Spaniard named by the Indians Kanopee, who had been shipwrecked near the mouth of the Columbia.

Other stories tell of red-haired Clatsop Indians, possibly descended from a red-haired Scotsman said to have survived a shipwreck in Nehalem Bay in December 1760. Another account dates this particular shipwreck in 1745.

There is evidence of even earlier shipwrecks. The Spanish supply ships often carried great quantities of beeswax to the missions, and when these ships were blown far off course and wrecked along the northern Pacific, the beeswax would wash ashore. Beeswax does not decay in saltwater or sand. Because it was common practice to stamp each block of wax with the year it was made, these blocks can date a shipwreck. Several have been found in the Nehalem, Oregon, area with the date 1679.

In 2013, the Beeswax Wreck Research Project, comprising students, archaeologists, and historians took up the search for a wrecked galleon off the coast of Manzanita, Oregon, according to an article in The Oregonian for Aug. 15, 2013. They planned to use sonar and a magetometer towed behind a 40-foot boat to search for a wreck they believe to the Santo Cristo de Burgos, which left Manila in 1693 and never reached Mexico. No wreckage ever was found. But beeswax pieces have been found on the beach. One large piece, now in the Nehalem Valley Museum, was found in the early 1940s. It is about 16 inches wide by 18 inches long and six inches thick. It bears the symbol of a shipper in Manila. Pollen in the wax has been shown to be from bees in the Philippines.

The Shark, Its Flag, And The Cannons

One of the most famous shipwrecks at the mouth of the Columbia River was that of the U.S.S. Shark, a Navy warship that visited in 1846. Its commander, Lt. Neil M. Howison, had been ordered to conduct a reconnaissance of the Oregon Territory, or at least that part of it that included the lower Columbia River, which he did after arriving in July, crossing the bar and anchoring in the estuary five miles from Cape Disappointment on the 18th of the month.

His report was not published until 1848, as his departure was delayed. There was a reason.

As the Shark sailed out of the Columbia on September 10, 1846, it was caught by the outgoing tide. The crew lost control in the swift current, and the ship foundered against an uncharted shoal near Clatsop Spit and began to break up. The ship did not sink immediately, and so there was time for the crew to abandon with just a few essentials and make it to the south shore.

Once on land their situation was not dire, no one died, but they were stranded. So Howison decided he and the crew would stay near the mouth of the river in hopes he could charter an outbound ship and reach the naval base at San Francisco. They built a small log house and named their temporary home Sharksville, after the ship. Word of the disaster traveled upriver to Fort Vancouver on the Columbia, where Howison had stayed during his reconnaissance duties, and Oregon City on the Willamette River, and soon British Hudson’s Bay Company workers began bringing them supplies. Read the account of a survivor, Burr Osburn, who wrote to the postmaster of Astoria in 1913 asking if anyone was still alive who remembered the Shark, and volunteering to tell his story.

For months the crew awaited a ship, and then, on October 16, 1846, an American merchant ship, the Toulon, arrived from Hawaii, known then as the Sandwich Islands, with news that the United States and the United Kingdom had signed, just that summer, a treaty establishing the long-disputed international boundary at the 49th Parallel. Since the Convention of 1818 between the United States and Great Britain, a follow-up to the Treaty of Ghent that ended the War of 1812, the Oregon Territory had been administered jointly by the two countries. Now, as a result of the Treaty of Oregon, the Oregon Territory – and Sharksville – were officially part of the United States.

As far as is known, the crew of the Shark were the first in the Oregon Territory to hear the news, and Howison was the first to fly the flag of the United States – the Shark’s flag – over the Oregon Territory, at Sharksville. He later donated the flag to the Governor of Oregon Territory, George Abernathy. In his letter accompanying the flag, dated December 1, 1846, Howison wrote:

“One of the few items preserved from the shipwreck of the late United States schooner Shark, was her stand of colors. To display this national emblem, and cheer our citizens in this distant territory by its presence, was a principal object of the Shark’s visit to the Columbia; and it appears to me, therefore, highly proper that it henceforth should remain with you, as a memento of parental regard from the general government.”

In response, Gov. Abernathy wrote, in a letter dated December 21, 1846:

“I received your esteemed favor of the 1st December, accompanied with the flags of the late U.S. schooner “Shark,” as a “memento of parental regard from the general government” to the citizens of the territory. Please accept my thanks and the thanks of this community for the (to us) very valuable present. We will fling it to the breeze on every suitable occasion, and rejoice under the emblem of our country’s glory.

Sincerely hoping that the “star spangled banner” may ever wave over this portion of the United States, I remain, dear sir, yours truly, Geo. Abernathy.

In November, Howison was able to charter the Hudson’s Bay Company ship Cadboro and returned to San Francisco, arriving in January 1847. A Court of Inquiry absolved him of blame for the loss of the ship.

The memory of the Shark remains today in the name of Cannon Beach, Oregon. It is near there, at Arch Cape, that portions of the deck of the Shark and three pieces of its artillery were found washed up on the beach, first just a month after the shipwreck, in October 1946, then again in 1863, 1898, and 2012. In all, three cannons have been recovered from the Shark, carefully cleaned and restored, and are now in museums at Cannon Beach and Astoria. An excellent, if brief, history of the Shark and the cannons is on the website of Offbeat Oregon. Also see the Wikipedia entry on the Shark.